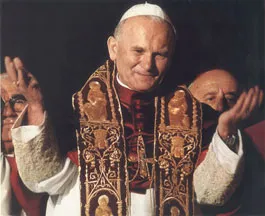

Photo: AP/Wide World Photos

One day in July 1944, as the Second World War raged throughout Europe, General William “Wild Bill” Donovan was ushered into an ornate chamber in Vatican City for an audience with Pope Pius XII. Donovan bowed his head reverently as the pontiff intoned a ceremonial prayer in Latin and decorated him with the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Sylvester, the oldest and most prestigious of papal knighthoods. This award has been given to only 100 other men in history, who “by feat of arms, or writings, or outstanding deeds, have spread the Faith, and have safeguarded and cham-pioned the Church.”

Although a papal citation of this sort rarely, if ever, states why a person is inducted into the “Golden Mili-tia,” there can be no doubt that Donovan earned his knighthood by virtue of the services he rendered to the Catholic hierarchy in World War II, during which he served as chief of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1941, the year before the OSS was officially constituted, Donovan forged a close alliance with Father Felix Morlion, founder of a European Catholic intelligence service known as Pro Deo. When the Germans overran western Europe, Donovan helped Morlion move his base of operations from Lisbon to New York. From then on, Pro Deo was financed by Donovan, who believed that such an expenditure would result in valuable insight into the secret affairs of the Vatican, then a neutral enclave in the midst of fascist Rome. When the Allies liberated Rome in 1944, Mor-lion re-established his spy network in the Vatican; fromthere he helped the OSS obtain confidential reports provided by apostolic dele-gates in the Far East, which included information about strategic bombing targets in Japan.

Pope Pius’ decoration of Wild Bill Donovan marked the beginning of a long-standing, intimate relation-ship between the Vatican and U.S. intelligence that continues to the present day. For centuries the Vatican has been a prime target of foreign espionage. One of the world’s greatest repositories of raw intelligence, it is a spy’s gold mine. Ecclesiastical, political and economic informa-tion filters in every day from thousands of priests, bishops and papal nuncios, who report regularly from every corner of the globe to the Office of the Papal Secretariat. So rich was this source of data that shortly after the war, the CIA created a special unit in its counterintelligence section to tap it and monitor developments within the Holy See.

But the CIA’s interest in the Catholic church is not limited to intelligence gathering. The Vatican, with its immense wealth and political influence, has in recent years become a key force in global politics, particularly with Catholicism playing such a pivotal role in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Unbeknownst to most Catholics, the Vatican, which carefully maintains an apolitical image, not only has a foreign office and a diplomatic corps, but also has a foreign policy. And with Polish Communists embrac-ing Catholicism and Latin American Catholics embracing communism, the U.S. government and particularly the CIA have recently taken a much greater interest in Vatican foreign policy. A year-long Mother Jones investigation has revealed a number of unlikely channels—both overt and covert—which the agency uses to bring its influence to bear upon that policy.

Since World War II, the CIA has:

- subsidized a Catholic lay organization that served as the political slugging arm of the pope and the Vatican throughout the Cold War;

- penetrated the American section of one of the wealthiest and most powerful Vatican orders;

- passed money to a large number of priests and bishops — some of whom became witting agents in CIA covert operations;

- employed undercover operatives to lobby members of the Curia (the Vatican government) and spy on liberal churchmen on the pope’s staff who challenged the political assumptions of the United States;

- prepared intelligence briefings that accurately pre-dicted the rise of liberation theology; and

- collaborated with right-wing Catholic groups to coun-ter the actions of progressive clerics in Latin America.

It was in this last regard that the CIA supported factions within the Catholic church that were instrumental in pro-moting and electing the current pope, John Paul II, whose Polish nationalism and anti-Communist credentials, they thought, would make him a perfect vehicle for U.S. foreign policy. John Paul’s recent trip to Nicaragua could not have been matched by any American’s for the contri-bution it made to President Reagan’s Central American initiative. And hopes are high in Washington, D.C., that the pope’s forth-coming trip to Poland, where 90 percent of the people are Catholic, will re1 spark the anti-Soviet upris-ing so vital to Reagan’s plans for Eastern Europe.

Dark Knight of the Soul

Every year in late June a bizarre ritual takes place in Rome. Men and women fly in from all over the world to participate in a cere-mony that has been performed for centuries. Next year, the assembled might find CIA director William Casey in their midst. And Casey could well be accompanied by former Secretary of State Alexander Haig.

If they make the journey, Casey and Haig will join a gathering of the world’s Catholic elite on St. John’s Day. Dressed in scarlet uniforms and black capes, brandishing swords and waving flags emblazoned with the eight-pointed Maltese cross, these Catholic brothers and sisters will, in an atmosphere of pomp and circumstance befitting a coronation, swear allegiance to the defense of the Holy Mother Church.

Casey and Haig are both members of the Knights of Malta, a legendary Vatican order dating back to the Crusades, when the “warrior monks” served as the mili-tary arm of the Catholic church. The knights, in their latter-day incarnation as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), are a historical anomaly. Although the order has no land mass other than a small headquarters in Rome, this unique papal entity holds the status of nation-state. It mints coins, prints stamps, has its own constitution and issues license plates and passports to an accredited diplomatic corps. The grand master of the order, Fra Angelo de Moj ana di Cologna, holds a rank in the church equal to a cardinal and is recognized as a sovereign chief of state by 41 nations with which the SMOM exchanges ambassadors.

But the real power of the order lies with the lay mem-bers, who are active on five continents. Nobility forms the backbone of the SMOM; more than 40 percent of its 10,000 constituents are related to Europe’s oldest and most powerful Catholic families. Wealth is a de facto prerequi-site for a knightly candidate, and each must pass through a rigorous screening. Protestants, Jews, Muslims and di-vorced or separated Catholics are ineligible.

“The eight-pointed white cross stands out everywhere as a symbol of charity toward mankind and as a comfort and consolation to the sick and the poor,” says Cyril Tou-manoff, official historian of the SMOM. In recent years its members have carried on the Hospitaler tradition of the original knights by supporting international health care and relief efforts. They proudly offer aid to the needy regardless of race, creed or religious affiliation.

But the needy aided by certain SMOM members in the late ’40s were some of the 50,000 Nazi war criminals who, with the assistance of the International Red Cross, were furnished fake Vatican passports and, in some cases, cleri-cal robes, and were smuggled on Bishop Alois Hudal’s “underground railroad” to South America. Among those was Klaus Barbie, the “butcher of Lyons.”

In 1948, the SMOM gave one of its highest awards of honor, the Gran Croci al Merito con Placca, to General Reinhard Gehlen, Adolf Hitler’s chief anti-Soviet spy. (Only three other people received this award.) Gehlen, who was not a Catholic, was touted as a formidable ally in the holy crusade against godless Marxism. After the war he and his well-developed spy apparatus—staffed largely by ex-Nazis—joined the fledgling CIA. Eventually, hundreds more Nazis ended up on the U.S. government’s payroll. Among them was Klaus Barbie.

“The CIA very early on made a decision that Nazis were more valuable as allies and agents than as war criminals,” > says Victor Marchetti, an ex-CIA officer who was raised a Catholic. Marchetti is disturbed by the role of the CIA and his church in perpetuating the Nazi outrage. “It gets a little crazy,” he said, “when you let one thing [anticommunism] take over to the extent that you forgive everything else.”

The SMOM had given a different prestigious award in 1946 to another high-level CIA operative, James Jesus Angleton. “It had to do with counterintelligence,” An-gleton told Mother Jones, when asked why he was chosen for such a distinction. During World War II, Angleton was head of the Rome station of the OSS. Later, on his return to Washington, he ran what was tantamount to the “Vat-ican desk” for the CIA. According to Angleton, the agency does not have a Vatican desk. Nor does it have an Israel desk, for that matter, yet Angleton also covered that area. The extreme sensitivity associated with Israel and the Vat-ican required that work relating to them be buried among Angleton’s counterintelligence staff, which was well-suited for such assignments.

During the early years of the Cold War, Angleton organ-ized an elaborate spy network that enabled the CIA to obtain intelligence reports sent to the Vatican by papal nuncios stationed behind the Iron Curtain and in other “denied” areas. This was, at the time, one of the few means available to the CIA of penetrating the Eastern Bloc.

According to previously classified State Department memoranda, Angleton rec-ommended that the CIA fund Catholic Action, an Italian lay organization headed by Luigi Gedda, a prominent right-wing ideo-logue who had also been honored by the knights. Gedda was a key operative in an effort undertaken by the CIA and the Vatican to “barricade the Reds” in the

1948 Italian elections. Only weeks before the election, it appeared the Italian Communist party would prevail. The CIA and the Vatican both feared the Communists might win unless drastic measures were taken.

At the behest of Pope Pius XII, Gedda mobilized a huge propaganda machine. More than 18,000 “civic commit-tees” were formed to get out the anti-Communist vote. The Christian Democrats scored a decisive victory. Catholic Action is credited with turning the tables.

Catholic Action continued to be a dominant factor in Italian politics throughout the Cold War. It had great influence on trade unions and youth groups in Italy-groups that were heavily sub-sidized by the CIA, then un-der the leadership of Alien Dulles. Christian Demo-cratic politicians and church figures were also among the beneficiaries of the CIA.’s largess, which exceeded $20 million per year in the 1950s. The agency provided “proj-ect money” to numerous priests and bishops, usually in the form of contributions to their favorite charities. Often, these prelates were unaware of the true source of these funds. “We would consider people of this sort as our allies,” recalls Victor Marchetti, “even though they may not consider themselves in any way allied with us.”

Amazing Grace

The American section of the Sovereign Mili-tary Order of Malta has about 1,000 mem-bers—including 300 “dames.” They repre-sent the vanguard of American Catholicism, the point at which the Vatican and the U.S. ruling elite intersect. “The Knights of Malta comprise what is perhaps the most exclusive club on earth,” Stephen Birmingharn, the social historian, has written. “They are more

than the Catholic aristocracy…[they] can pick up a telephone and chat with the pope.”

And who are the American Knights? Mother Jones managed to obtain part of the secret membership list. On it we found some famil-iar names: Lee lacocca of Chrysler; Spyros Skouras, the shipping magnate; Robert Abplanalp, the aerosol tycoon and Nixon confidant; Barren Hilton of the hotel chain; John Volpe, former U.S. ambassador to Italy; and William Simon, who served as both treasury secretary and energy czar in the 1970s. At least one former envoy to the Vatican, Robert Wagner (the ex-mayor of New York), and the current emissary to the Vatican, William Wilson, are also members of the Knights of Malta. But there is one institution that stands out as the center of the SMOM in the United States—W.R. Grace & Company. J. Peter Grace, the company chairman, is also president of the American section of SMOM. No less than eight knights, including the chancellor of the order, John D.J. Moore (who was ambas-sador to Ireland under Nixon and Ford), are directors of W.R. Grace.

J. Peter Grace has a long history of involvement with CIA-linked enterprises, such as Radio Liberty and Radio Free Europe, which was the brainchild of General Rein-hard Gehlen. He is also the board chairman of the Amer-ican Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD), which has collaborated with multinational corporations and their client dictatorships in Latin America to squelch independent trade unions. Up to $100 million a year of CIA funds were pumped into “trustworthy” labor organi-zations such as AIFLD, whose graduates, according to AIFLD executive director William Doherty, were active in covert operations that led to the military coup in Brazil in 1964. During the early 1970s, Francis D. Flanagan, the Grace repre-sentative in Washington, D. C., was a member of ITT’s “Ad Hoc Committee on Chile,” which was instrumental in planning the overthrow of Salvador Allende. AIFLD’s National Workers’ Con-federation subsequently served as the chief labor mouthpiece for the Pinochet junta.

There are many other knights with CIA connections. Clare Boothe Luce, for example, the grande dame of American diplomacy, served as a U.S. ambassador to Italy in the 1950s and is now a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which oversees covert opera-tions. William Buckley, Jr., a former CIA operative and the editor of the National Review, is a member, as is his brother James, a former senator from New York and now undersecretary of state for security assistance.

Targeting the Pope

The American section of the SMOM is one of the main channels of communication be-tween the CIA and the Vatican. Of course, neither party will acknowledge this. “The Knights of Malta is an honorific society of Catholics. That’s all it is. … It has no political function,” asserts former CIA director William

Colby, who declined an invitation to join the illustrious order. (“I’m a little lower key,” he confessed.)

Technically speaking, Colby is correct; the knights do not have an explicit political function. They would never approach the Vatican with a message from the CIA. Nor would the Vatican ever openly ally itself with the political aims of the CIA. “Obviously, this is a dynamite type of proposition,” explains Victor Marchetti. “I’m sure that in the clandestine area there was real consideration of how to influence the Vatican, but you’ll never find a paper trail within the agency establishing an operational objective. A covert action of this sort is a very complex and sophisticated sort of thing…How much pressure the CIA would dare to exert on the Vatican is debatable. It would have to be done indirectly, on an informal basis.”

This is where the American section of the SMOM fits in. “They all belong to the same club,” says Marchetti. “One happens to be the director of the CIA, and another is a cardinal. When they get together and fraternize on a social basis, they exchange ideas and opinions as private indi-viduals. But how do you separate the private individual from the professional?”

During the 1950s and the early 1960s, relations between the U.S. and the Vatican were conducted largely through Francis Cardinal Spellman, the “Grand Protector and Spir-itual Advisor” to the SMOM’s American wing. An ultra-conservative ideologue, Spellman served as the right arm of Pope Pius XII and was a vocal supporter of U. S. military involvement in Vietnam.

But relations have not always been smooth, because Vatican policy has not always pleased American knights. In the early 1960s, Pope John XXIII took major steps to liberalize the church and to open a dialogue with the East. By doing so, he shifted papal policy from the strict anti-Communist line of his predecessor, Pius XII.

John XXIII felt that the Vatican had to adopt a more flexible posture—both socially and politically—if the church was to endure as a relevant institution. His attempts at rapprochement with the Soviet Union caught everybody by surprise and sent Vatican watchers at the CIA into a frenzy. But the agency had to step up its intelligence ac-tivity in the Vatican most cautiously, as the Kennedy ad-ministration was bending over backward to avoid any overt association with the Holy See. Kennedy, America’s only Catholic president, was so consumed by the possibility of a Protestant backlash that he rebuffed the pope’s efforts to mediate a thaw in East-West relations. Meanwhile Khrushchev, the supposed atheist, welcomed the pontiffs diplomatic overtures.

In May 1963, John McCone, a member of the SMOM and then director of the CIA, received a memorandum from James Spain, of the agency’s Office of National Esti-mates, on the ramifications of Pope John’s policies. There is “no doubt,” wrote Spain in the recently declassified 15-page memo, entitled “Change in the Church,” “that vig-orous new currents are flowing in virtually every phase of the church’s thinking and activities. . . . [this has] resulted in a new approach toward Italian politics which is permis-sive rather than positive.”

When Spain visited the Vatican, posing as a scholar on a foreign service grant, he voiced his concerns about major gains made by the Italian Left in the 1963 election. Many felt the Left’s success was attributable to Pope John’s conciliatory attitude toward the Communists. This was the first election in which the Christian Democrats were not officially endorsed by the Italian Bishops’ Conference. The pope had insisted upon maintaining a neutral stance so as not to jeopardize his Soviet initiative.

Speaking with officials of the Curia, Spain discovered a great deal of discontent regarding the direction in which the church was moving. Some even suggested to him that the pope was “politically naive and unduly influenced by a handful of ‘liberal’ clerics.” He heard tales about “the moral and political unreliability of [the pope’s] young col-laborators.” Among those who were particularly concerned by Pope John’s policies, according to Spain’s report to McCone, were members of the Roman aristocracy and the papal nobility, who, according to Spain, had lost many of their traditional privileges when Pius XII died.

A Holy Mole

John McCone now took a personal as well as professional interest in the Vatican situation. Thomas Kalamasinas, the station chief in Rome, was instructed to raise the priority of the Vatican spying operation. But the CIA ran into a snag when it learned that some of its best contacts — for example, the conservative prelates who held key posts in the Extraordinary Affairs Section of the Papal Secretariat, which was responsible for the implementation of Vatican foreign policy — were shut out by John XXIII’s tendency to circumvent his own bureau-cracy when dealing with the Russians. The pope evidently feared that his diplomatic efforts might be sabotaged by some Machiavellian monsignor. Thus, he pursued his goal outside the normal channels of the Curia. A small group of trusted collaborators served as couriers for the pope, who rarely used the telephone to speak with anyone outside the Vatican for fear that the line might be tapped.

When John XXIII died in 1963, CIA analysts prepared a detailed report predicting that Giovanni Cardinal Montini of Milan would be the next pope. They were right. But more amazing than the prediction is the fact that the agency was later able to confirm the identity of John’s successor in advance of the official announcement. How was the CIA privy to such information, given the exces-sive secrecy surrounding the College of Cardinals during a papal election? Italian intelligence sources maintained that the CIA bugged the conclave. Time magazine correspondent Roland Flamini speculates in his book Pope, Premier, President that the agency may have developed an informant among the car-dinals, who communicated with the CIA through a hidden electronic transmitter.

Giovanni Montini was no stranger to American intel-ligence. During World War II, he worked in the Office of the Papal Secretariat and passed information to a grateful OSS. Later he had a falling out with Pope Pius XII and was “exiled” to Milan. This news was well-received by Vatican watchers within the CIA, who had pegged Montini as a “liberal” Neverthe-less, he remained an important figure in the church, with extensive religious and political contacts. Every CIA sta-tion chief in Italy made a point of getting to know him, and CIA “project money” was donated to various orphanages and charities whose principal benefactor was the archbishop of Milan.

When Montini became pope, taking the name Paul VI, he continued to pursue an open-door policy with the Soviet Union. Leaders from Eastern Europe were received on state visits (Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko had seven meetings with Pope Paul), and many Vatican officials traveled to Moscow for

talks. Toward the end of his papacy, Paul VI let it be known that he was not averse to a center-left coalition of the Italian Communist party and the Christian Democrats. This infuriated hard-line elements within the CIA. In 1976, the Georgetown University Center for Strategic and International Studies, a conservative think tank, spon-sored a conference on the Communist threat in Italy. Panelists included former CIA director William Colby (who was station chief in Rome during the 1950s); Clare Booth’e Luce, who was U.S. ambassador to Rome at the same time; Ray Cline, another ex-CIA official; and John Connally, then a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. Their message, which doubtless reached the pope, was unequivocal: Eurocommunism.was a threat to U.S. security, and Marxists must never be allowed to participate in the Italian government.

This was not the first time pressures from outside the Vatican were exerted on Pope Paul. In 1967, Paul authored a controversial encyclical, Populorum Progressio, in which he criticized colonial repression and recom-mended economic and social remedies that were widely interpreted as a denunciation of capitalism. Shortly thereafter, an international group of businessmen asked the Holy Father to “clarify” his economic views. The delegation included George C. Moore, then chairman of Cit-ibank. Pope Paul subsequently issued a statement in which he denied any hostility toward private enterprise.

Liberation Theology

Classified CIA studies prepared throughout the 1960s with titles such as “The Catholic Church Reassesses Its Role in Latin America” depicted a church with a commitment to economic and political reform. The studies foresaw the emergence of “liberation theology,” which would provide the theoretical basis for a “peo-ple’s church” that would establish itself in Latin America in the early 1970s. Pope Paul helped fulfill the CIA’s predictions by appointing socially conscious bishops and by encouraging church activists who opposed South Ameri-can military dictatorships. Paul’s gesture toward the Left was, no doubt, a calcu-lated maneuver directed at the hearts and minds of the Catholic masses. Political reality demanded the promotion of a palatable Christian alternative, lest the brethren put their faith in “Saint” Fidel or Che Guevara. At first, some CIA officials favored Paul’s reformist approach as an effective anti-dote to communism, but as time went by a consensus developed inside the agency that Paul VI had gone too far, that his strategy would backfire and play into the hands of the Marxist revolutionaries.

As Pope Paul VI grew older, great concern devel-oped within intelligence circles over who would succeed him. Agency analysts drew up profiles on leading papal candidates, identifying those who were likely to be sympathetic to American interests. In 1977, Terence Cardinal Cooke, the current Grand Protector and Spiritual Advisor of the SMOM, traveled to Eastern Europe to discuss the matter of choosing a candidate to succeed Pope Paul. During this sojourn, Cardinal Cooke met personally with Karol Cardinal Wojtyla of Krakow, who was noted for his anti-Communist leanings. Cooke’s coalition-building efforts bore fruit the following year, after Paul’s successor, Pope John Paul I, died, having served scarcely a month. (There were widespread rumors that he had been poi-soned.) In October 1978, the Vatican’s Sacred College of Cardinals elected Karol Wojtyla pontiff.

The New Inquisition

October 1976. Father Patrick Rice is dragged from his prison cell in Buenos Aires by members of the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance, a paramilitary police agency. He has already been held incommunicado for several days and has been beaten ruthlessly. The routine is about to begin again: electric shock treatment, water torture that makes him feel as if he is drowning. Throughout the ordeal he hears the screams of other prisoners. Eventually he is transferred to police headquarters, in which are passage walls covered with swastikas.

“My Christian faith became very real to me,” remem-bers the priest, who survived two months of captivity and recovered in a psychiatric ward.

Father Rice is one of the lucky ones. During the past 15 years, 1,500 priests, nuns and bishops have been murdered, imprisoned, tortured or expelled from Latin America. “Any Christian who defends the poor,” says Rice, “can expect to be persecuted and mistreated by the security police.”

Only a generation ago, the persecution of the Catholic clergy would have been unthinkable, for the church had always sided with the reactionary sectors of society — the wealthy landowners and the military. But Pope John XXII’s vision of Catholicism as a community of believers in and of the world sparked major reforms. His policies set the stage for the historic gathering of Latin American bishops that took place during the papacy of Paul VI at Medellin, Colombia, in 1968. It was at this conference that the liberation theology predicted by the CIA earlier in the decade was born. The bishops called upon the church to “defend the rights of the oppressed” and recognize a “preferential option for the poor” in the struggle for social justice.

Liberation theology came to life in the form of thou-sands of grassroots Christian communities that sprang up throughout Latin America, where nine out of ten people are Catholic, and eight out of ten are destitute. Within these groups, religion became less a ritualistic phenom-enon and more an inspiration to clergy and laity attempting to remove the yoke of oppression from the poor. Some priests even began to align themselves with the left-wing guerrillas engaged in armed struggle against U.S.-backed regimes. “The Christian base communities are the greatest threat to military dictatorships throughout Latin America,” said Maryknoll Sister Ita Ford in late 1980, three weeks before she, two other American nuns and Jean Donovan, a lay missionary worker, were brutally murdered in El Salvador.

The CIA was quick to recognize the “subversive” potential of liberation theology and mounted an extensive cam-paign to undermine the new movement. The agency’s strategy, formulated during the late 1960s and early ’70s, when Richard Helms was director, was to exploit the polarization between the activist clergy and those who still identified with the established order (the holdovers from the Cold War era, when missionaries were routinely em-ployed as agents and informants). Toward this end, as Penny Lernoux documents in her book Cry of the People, the CIA used right-wing Catholic organizations in Latin America to harass outspoken prelates and political reformers. The agency also trained and financed police agencies responsible for the torture and murder of bishops, priests and nuns, some of them U.S. citizens.

In 1975, the Bolivian Interior Ministry — a publicly acknowledged subsidiary of the CIA — drew up a master plan for persecuting progressive clergy. The scheme, dubbed the “Banzer Plan” — after Hugo Banzer, Bolivia’s right-wing dictator (who retained Klaus Barbie as his security advisor) — was adopted by ten Latin American governments. The plan involved compiling dossiers on church activists; censoring and shutting down progressive Catholic media outlets; planting Communist literature on church premises; and arresting or expelling undesirable foreign priests and nuns. The CIA also funded anti-Marxist religious groups that engaged in a wide range of covert operations, from bombing churches to overthrowing constitutionally elected governments. The success of the Banzer Plan was vividly demonstrated in San Salvador in the late 1970s, when an anonymous group distributed a leaflet that read: “Be a Patriot! Kill a Priest!” A series of clerical assassinations followed, culminating in the murder of the progressive and pop-ular Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

More recently, the Reagan administration has sharp-ened its attack on progressive elements of the church, both at home and abroad. The Santa Fe Report, prepared for the Council for Inter-American Security and presented in 1980 to the Republican Platform Committee by a team of ultraconservative advisors, states that “U.S. foreign policy must begin to counter (not react against) liberation theol-ogy as it is utilized in Latin America by the ‘liberation theology’ clergy.” In order to garner support for this policy, the Institute for Religion and Democracy (IRD), an interdenominational organiza-tion, was established in 1981 with funding from right-wing institutions, including the Smith ‘Richardson and Sarah Scaife foundations, both of which have served as CIA financial conduits. The IRD unleashed a propaganda drive against church activists at the forefront of domestic opposition to U.S. aid to the government of El Salvador and other repressive regimes in Latin America. The IRD campaign has been highly successful, even reaching the pages of Reader’s Digest, from where it was picked up by 60 Minutes.

The Holy Mafia

Under Casey, the CIA has continued its attack on progressive elements within the church. Casey is also a member of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

Of all the groups that are engaged in the U.S.-sponsored campaign against libera-tion theology, none has played a more significant role than Opus Dei (“God’s Work”). A fast-growing Catholic lay soci-ety whose political activities are shrouded in secrecy, Opus Dei was founded in 1928 by Jose Maria Escriva de Balaguer, a young Spanish priest and lawyer. Escriva espoused complete obedience to church dogma. Today, there are more than 70,000 members of the order in 87 countries. Only a small percentage are priests. The rest are mostly middle- and upper-class businessmen, professionals, military personnel and government officials. Some are university stu-dents. The members con-tribute regularly to the group’s financial coffers and are encouraged to practice “holy shrewdness” and “holy coercion” in an effort to win converts.