Commodification of Time in Michael Ende’s Momo

Materialization of time and remarks of consumerism in Michael Ende’s Momo

Momo is a homeless girl, who runs away from orphanage to an uncertain city where Momo takes place. The plot mainly adopts Momo’s adventures of gaining the stolen time back from the time-thieves, who are called “The Grey Gentlemen”. Those Gentlemen continue to exist by smoking rolled cigar made of other people’s hour-lilies (Goodhew and Loy, 98). The Grey Gentlemen promise people to give more time in the future but with one condition which is to save time as much as they can (Goodhew and Loy, 99). The Grey Gentlemen ask their clients to save time “by speeding up work, cutting off from social time and eliminating all joy from their life (Goodhew and Loy, 99). However the more people saved time the less they had (Ende, 41).

“Calendars and clocks exist to measure time, but that signifies little because we all know that an hour can seem an eternity or pass in a flash according to how we spend it. Time is life itself and life resides in human heart. (32)” The criticism of materializing time, using it as a commodity leads almost whole novel Momo. The novel itself stands against using time as a commodity by constantly repeating that “time is life itself and life resides in the human heart (32).” Michael Ende criticizes negative effects of materializing time, and consumerism throughout Momo with characters that seem to be very symbolic.

Goodhew suggests that problem today is not so different from what Momo implies. She suggests that “problem is commodification, which tends to convert everything into marketable resources appreciated only according to their exchange value. (Goodhew and Loy, 100)” Goodhew proposes that The Grey Gentlemen enforce time to people as a commodity which can be “saved and invested” (Goodhew and Loy, 101).

Before the arrival of The Grey Gentlemen, people lived in harmony, peace without a rush. For instance Momo’s friend Beppo whose job is to sweep streets has a very symbolic conversation with Momo. Beppo tells Momo that how hard it is when there is a “terribly” long street ahead of him to sweep. He says that he feels rushed, panicked thinking that he can never sweep it at once. However Beppo adds that this is not how a street should be swept by saying that one must think street as a whole, “concentrating on the next breath, next stroke of the broom, and the next”. He says that this is how someone makes a good job (21). The symbolism here resolves as the novel progresses. Long streets that Beppo tells about can be interpreted as life, and life should not be rushed, should be thought as a whole since “it resides in human heart” (32).

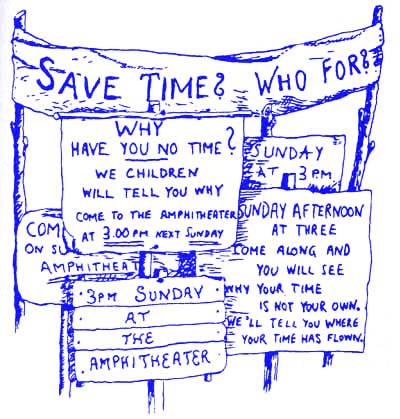

The Grey Gentlemen are depicted with constant repetition of the word “grey”. The colour grey is used very symbolically to describe those gentlemen’s lifeless, dull personality. They wear grey suits; they have grey notebooks, cigars and briefcases. Those Gentlemen also have “expressionless grey voice” (33). After their arrival of these Gentlemen the city and the people become as dull as they are. Levine argues that “when the tempo of the events are fast the duration of the time compress” (Levine, 41), it is the same for what happens in Momo. People are so busy by working more and saving more time they do not have time to realize they are actually saving nothing. Goodhew explains that while the barber Figaro was feeling depressed and questioning his value, one of the grey men appears and persuades him to donate his time to time saving bank by cutting off every activity that makes his life better such as spending time with his elder mother and reading books (99). The Grey Gentlemen do not only persuade Figaro but whole town. Materialization of time becomes so widespread that people read notices like “Time is money, save it! or “Time is precious do not waste it!” everywhere (40). What The Grey Gentlemen are doing is actually “time-flies” concept that Glen H. Brodowsky explains by saying that any “enjoyable activity cease to be less important to accomplish a specific task” (Brodowsky et al 251). Glen H. Brodowsky also refers to this concept as “viewing time in polychronic manner” (Brodowsky et al. 251).

As The Grey Gentlemen take over city, they begin to numb children with toys that kill their imagination since they were designed into tiniest detail, “leaving them mesmerized but bored” (42). Children were surrounded by lots of toys that they could not even play with (42). Such as space rockets which had wings but flew nowhere or “model robots that did nothing but waddle along with eyes flashing and heads swiveling” (42). With endless choice of toys, Goodhew points out that The Grey Gentlemen teach children “the economic lesson” (Goodhew and Loy, 99) that “there is always something left to wish for” (52). These Gentlemen also try to trick Momo with a doll that has a “never-ending” wardrobe of clothes (Goodhew and Loy, 99). Goodhew narrates that because of the children’s ability “to live in the present” The Grey Gentlemen see them as a threat (Goodhew and Loy, 99). The Grey Gentlemen find solution to this threat by having them put in “prison like” child deposits which Goodhew argues that they stand for modern day care centres, and schools (Goodhew and Loy, 99).

Michael Ende shows how people “reduce time to a pure number” (Aveni, qtd in Goodhew and Loy, 101), and he stands against materialization of time by constants remarks of how time “resides in human heart” (32). As it is mentioned above The Grey Gentlemen live on stolen time, they smoke cigars made out of stolen hour-lilies. At the end of Momo, Momo saves time from The Grey Gentlemen by finding stolen, frozen hour-lilies. Those hour- lilies, source of time, grows in human heart and once they are plucked from their owner’s heart they cannot die because “they are not withered” but they cannot survive either because they are parted from their owner (135). Momo, a seemingly children’s novel, adopts more serious subjects more than Momo’s adventure of saving time, such as consumerism, and commodification of time. Momo also explains commodification of time in relation to consumerism by explaining how people never seemed to satisfy with time and try to save more and more. Momo basically is a story of how “present is crushed by the pull of past and future (Winterson, 65).

Works cited

Brodowsky, H. Glen, Beverlee B. Anderson, Camille P. Schuster, Ofer Meilich, and M. Ven Venkatesan. “If Time Is Money Is It a Common Currency? Time in Anglo, Asian, and Latin Cultures.” Journal of Global Marketing 21.4 (2008): 245-57. Taylor & Francis Online. Web. 23 Dec. 2014.

Ende, Michael, and J. Maxwell Brownjohn. Momo. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985. Print.

Goodhew, Linda, and David Loy. “Momo, Dogen, And The Commodification Of Time.” Kronoscope 2.1 (2002): 97-107. Academic Search Complete. Web. 27 Dec. 20

Levine, Robert. (1997) A Geography of Time, New York: Basic Books.

Winterson, Jeanette. Weight: The Myth of Atlas and Heracles. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2005. Print.