There's a bacteriophage that turns bacteria into “liquid crystals.”

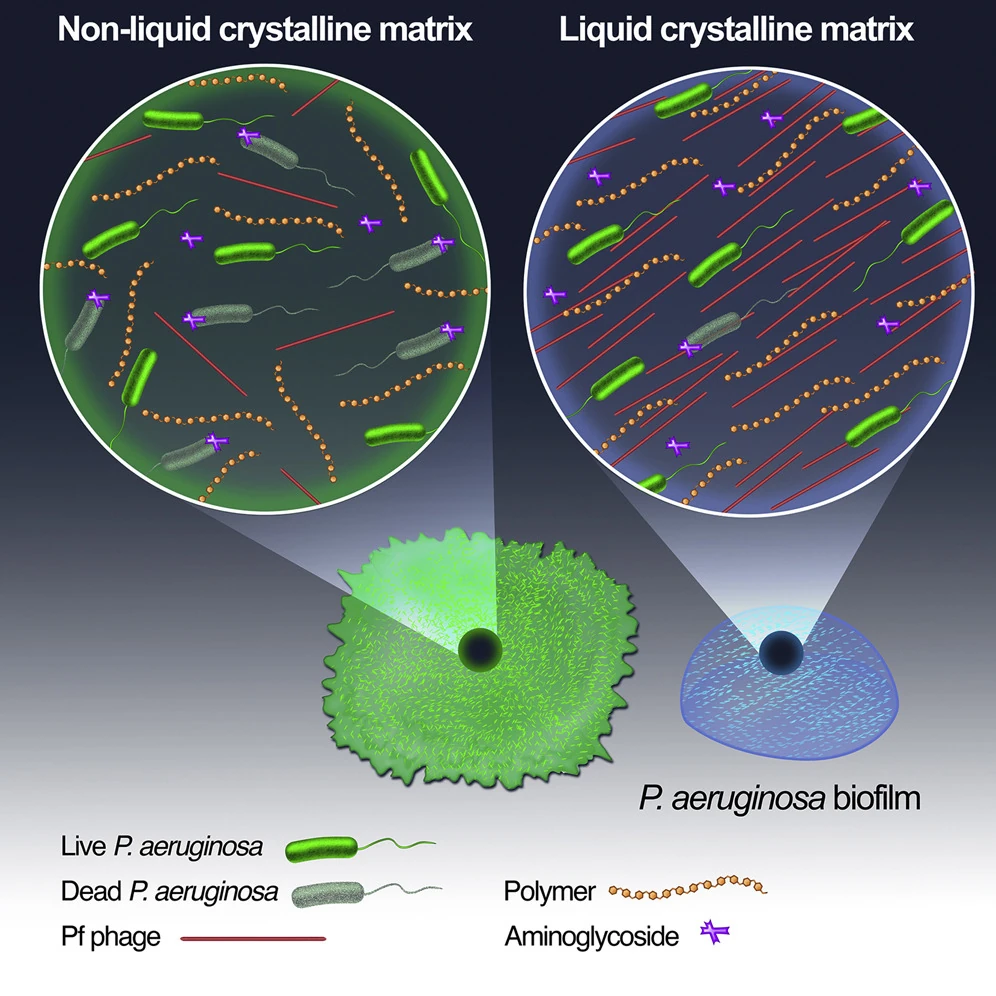

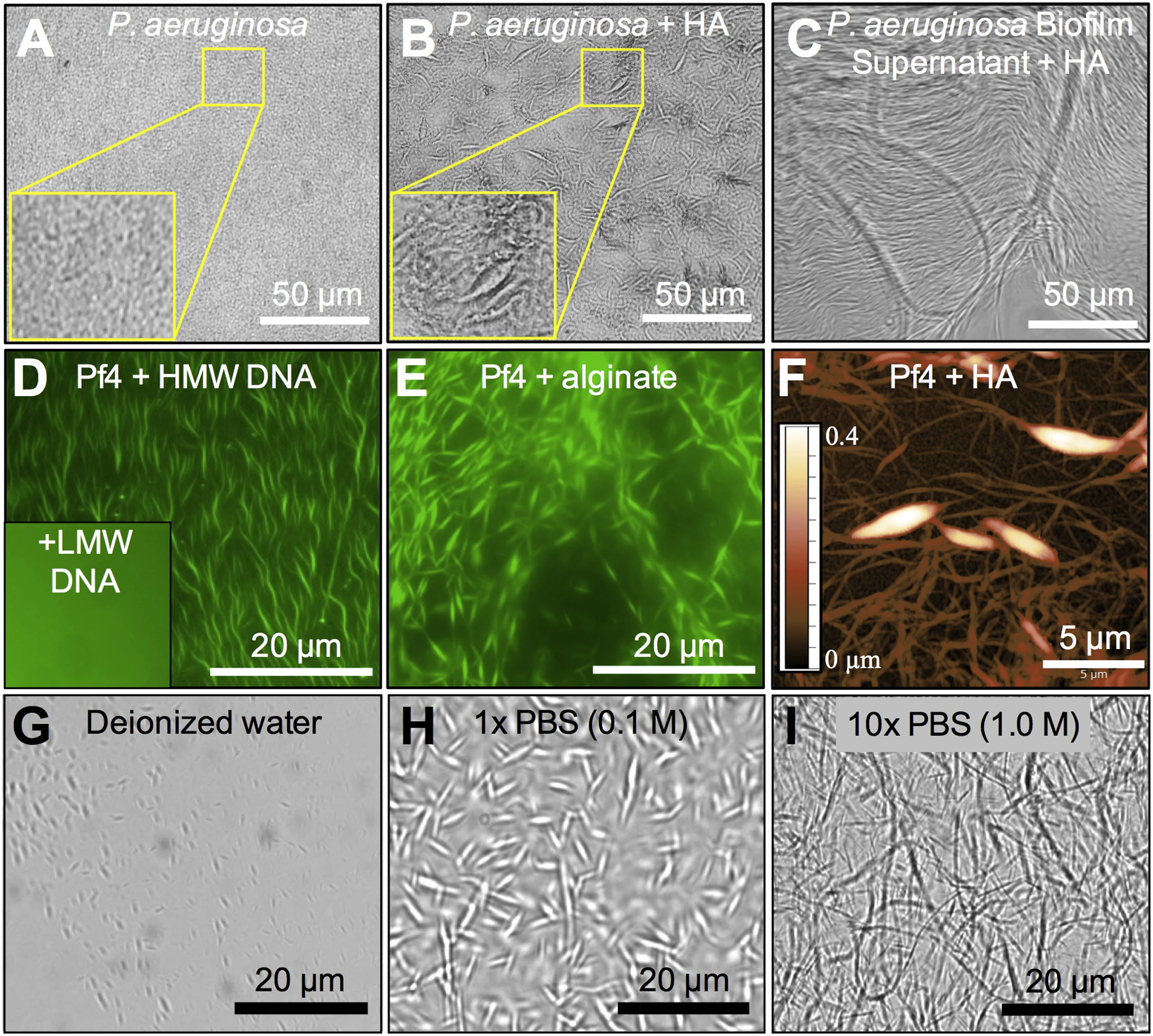

Specifically, Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria make Pf phages, which are rod-shaped, negatively-charged, and measure about 2 micrometers in length (roughly the length of an E. coli cell). These phages leave the cells and enter their surroundings. There, they mix with polymers, also secreted by the cells, to form a crystalline matrix.

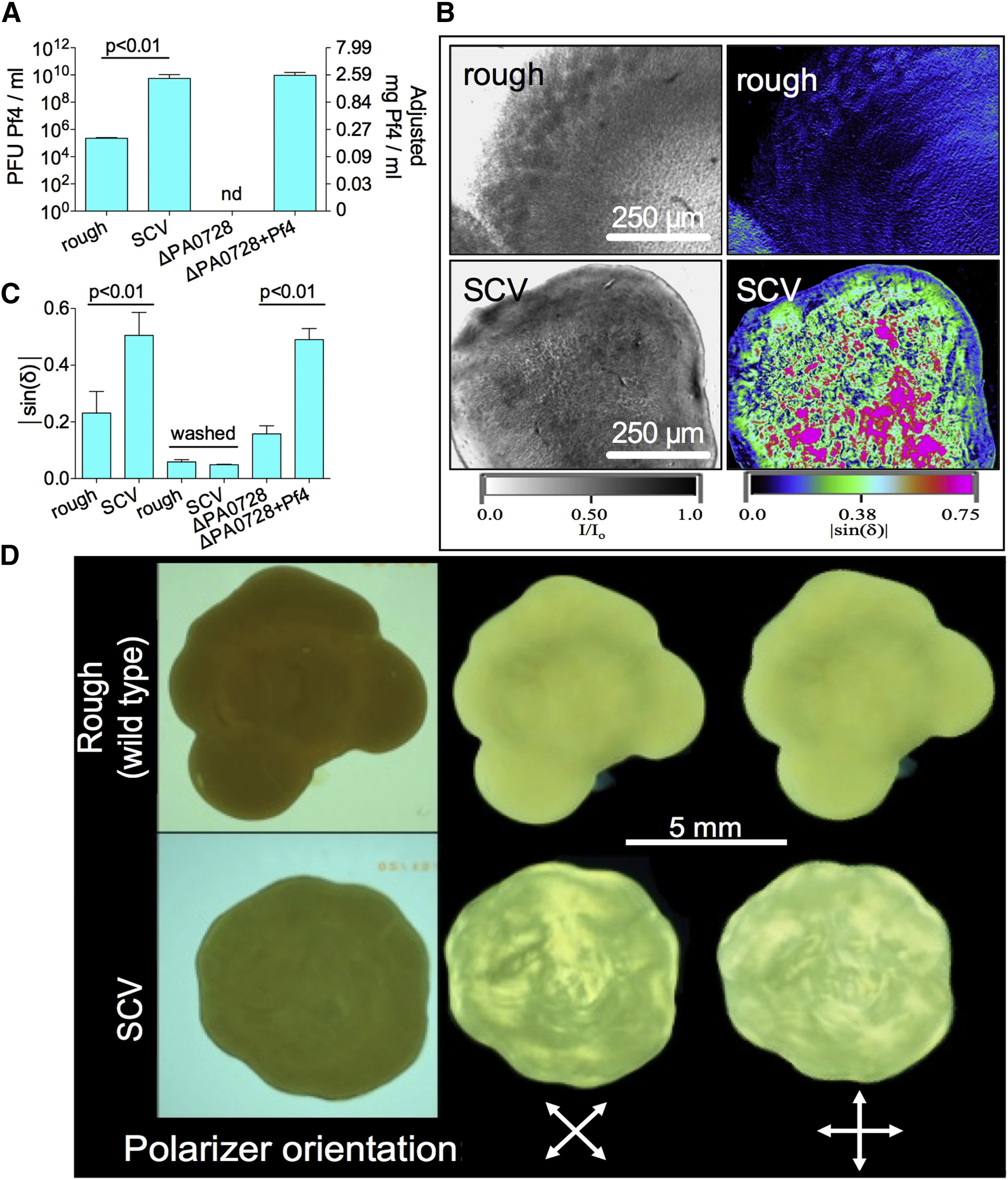

Surprisingly, this is good for the cells. Although the phages kill some of them, it also makes their biofilms stickier and able to withstand certain antibiotics. These bacteria + phages are prevalent in cystic fibrosis patients; they've formed a sort of symbiotic relationship.

The Pf phages are made from thousands of repeating copies of a coat protein, called CoaB, which wraps around a single-stranded, circular DNA genome. These genes are integrated directly on the bacterial chromosome.

The bacteria “turn on” these phage genes when placed in a viscous environment with low oxygen levels. This is like a trigger to start forming a biofilm. And the cells make a lot of phages; about 100 billion per milliliter.

These liquid crystals form because of a physics principle called “depletion attraction.” If you just mix a bunch of loose or flexible polymers together (such as long carbon chains) they will not form a liquid crystal. But if you mix stiff rods (the phages) with loose polymers at a high enough concentration, the polymers will force the phages close together to create a material that flows like a liquid despite being ordered like a crystal. See the video below.

These liquid crystal biofilms are hard to get rid of. The negatively-charged phages block many antibiotics (like aminoglycosides, which are positively-charged) from entering cells. Liquid crystals also retain water, so these biofilms can survive on drier surfaces.

Paper: Filamentous Bacteriophage Promote Biofilm Assembly and Function