How 20 Smuggled Chinese Hamsters Built a Pharmaceutical Empire

Chinese Hamster Ovary, or CHO, cells are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry. And, incredibly, these cells can be traced back to just twenty hamsters that were packed into a crate and smuggled out of China in the 1940s.

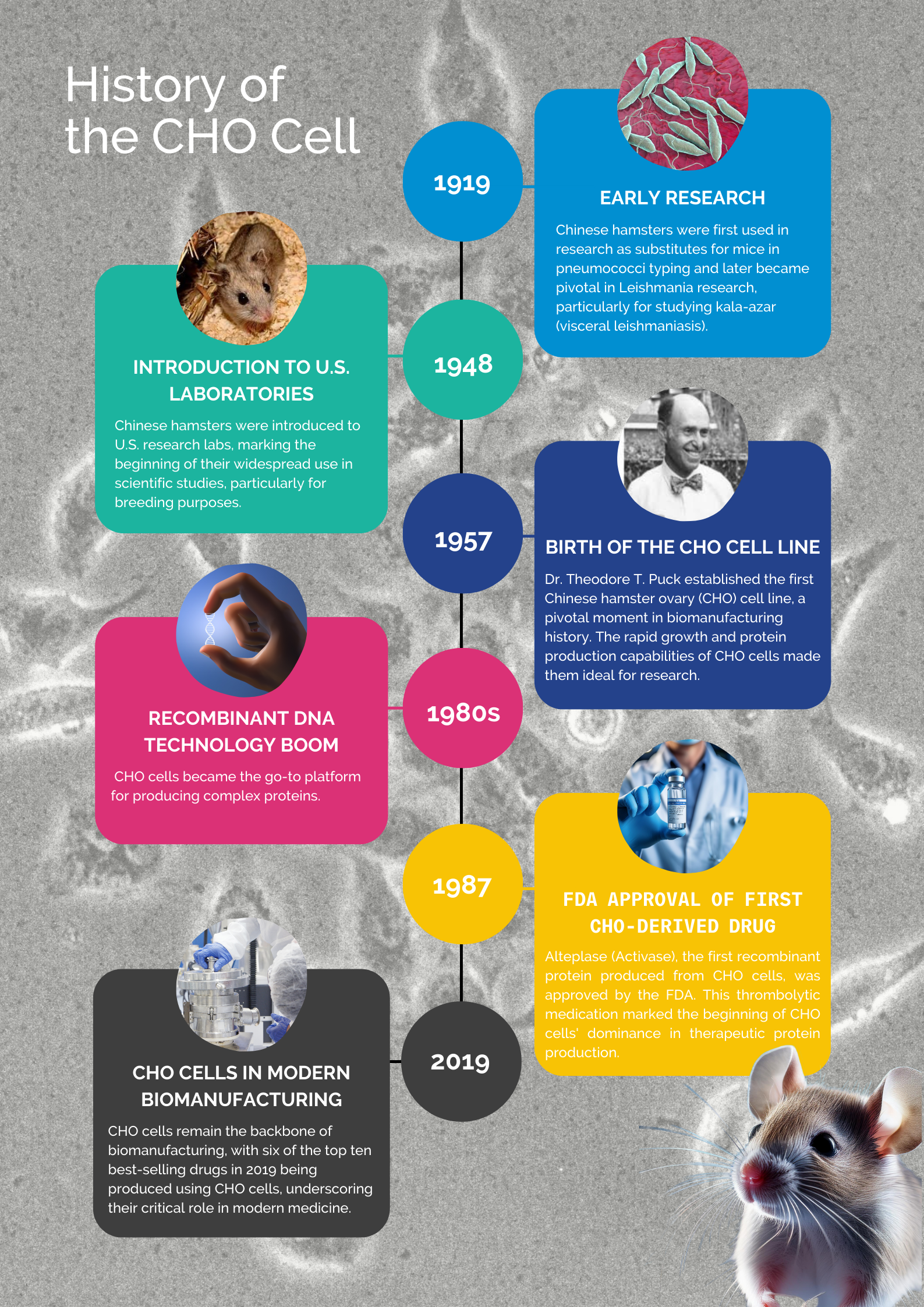

Chinese scientists had been using these hamsters — native to northern China and Mongolia — to study pathogens since at least 1919. The hamsters were unusually well-suited to scientific research because they have short gestation periods (18-21 days), a natural resistance to human viruses and radiation, and it was thought, early on, that they possessed just 14 chromosomes, making them easy to work with for mutation studies. (They actually have 22 chromosomes.)

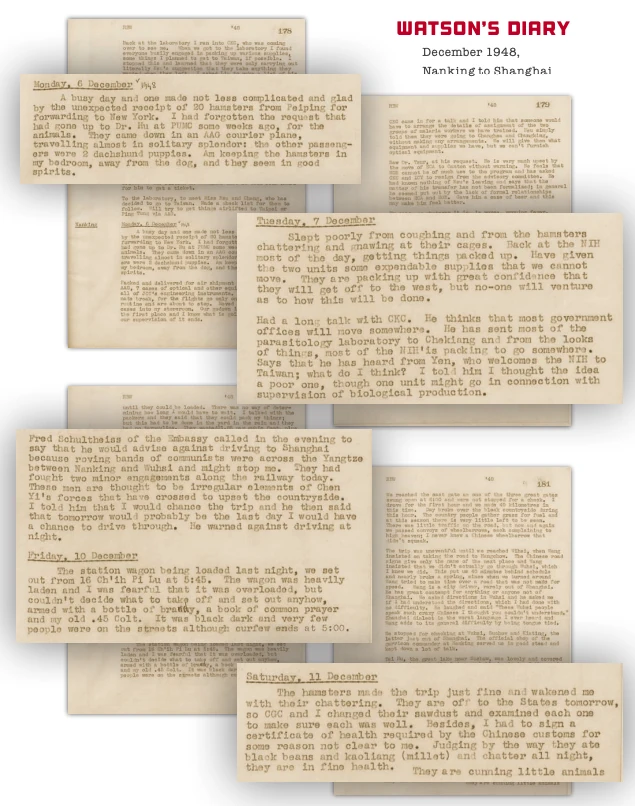

During the Chinese civil war, a rodent breeder in New York named Victor Schwentker worried that, if the Communists won the war, he’d never be able to get his hands on these special rodents. So in 1948, Schwentker sent a letter to Robert Briggs Watson, a Rockefeller Foundation field staff member, and asked him to “acquire” some hamsters so he could begin breeding them.

Watson collected ten males and ten females and packed them into a wooden crate with help from a Chinese physician (who was later imprisoned for this act). Watson slipped the crate out of the country on a Pan-Am flight from Shanghai, just before the Communists took control.

In New York, Schwentker received the hamsters and then began breeding and selling them to other researchers.

In 1957, a geneticist named Theodore Puck, intent on creating a new mammalian “model system” for in vitro experiments, learned about the Chinese hamster and contacted George Yerganian, a researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, to obtain a specimen. Yerganian shipped Puck one female hamster.

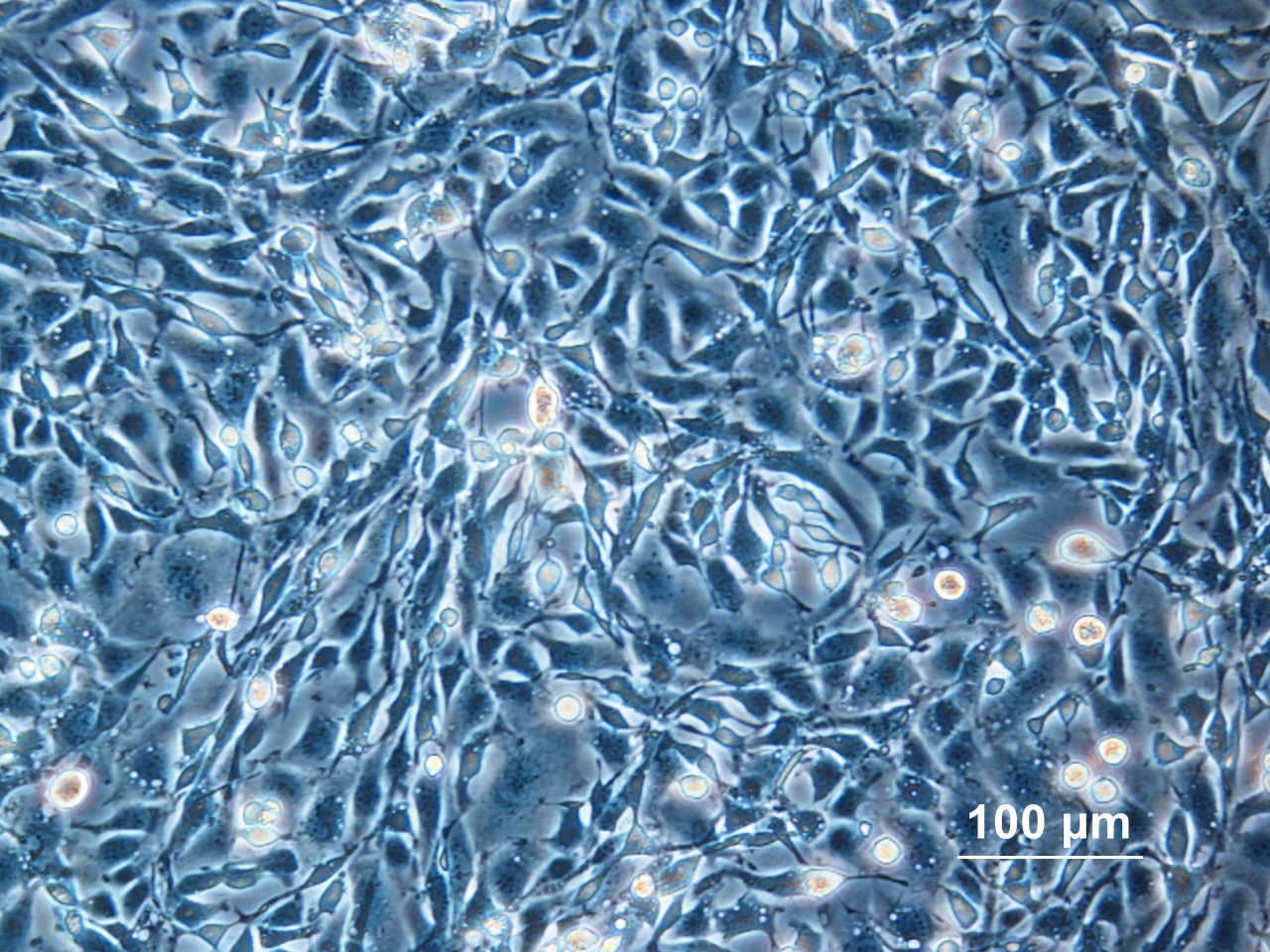

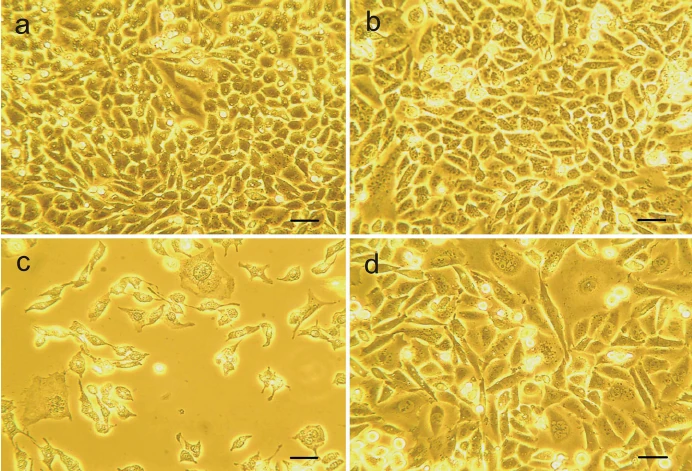

Puck took a small piece from this hamster’s ovary, plated the cells onto a dish, and passaged them repeatedly. He eventually isolated a clone that could divide again and again; an “immortalized” CHO cell with a genetic mutation that rendered it immune to normal senescence.

Today, descendants of these immortalized CHO cells make about 70 percent of all therapeutic proteins sold on the market, including Humira (USD 21 billion in sales in 2021) and Keytruda ($17 billion). Many of these drugs are monoclonal antibodies, or Y-shaped proteins that lock onto, and neutralize, foreign objects inside the body.

CHO cells are well suited to biotherapeutics because they can perform a biochemical reaction called glycosylation. Many human proteins, including antibodies, are decorated with chains of sugars that control how they fold or interact with other molecules in the body. Only a few organisms, mostly mammalian cells and certain yeasts, can do this chemical reaction.

I first learned about this history from a really spectacular article in LSF Magazine, called "Vital Tools: A Brief History of CHO Cells." I recommend it. (You can find it with a quick search.)