tag > China

-

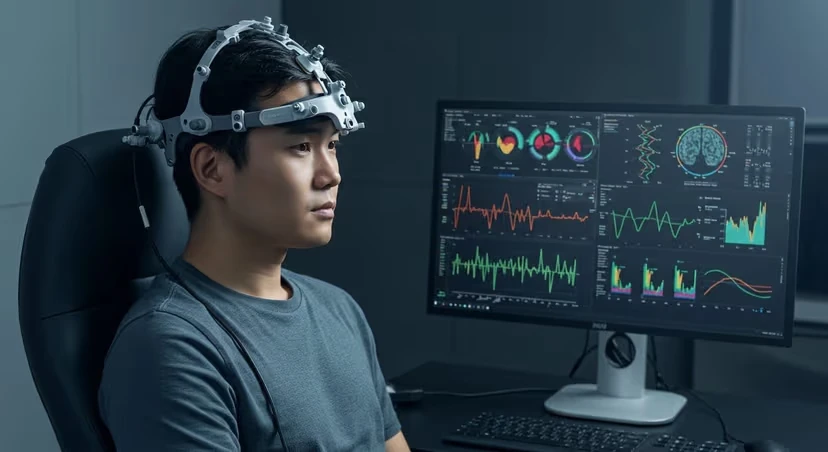

China pushes to lead brain-computer interface market by 2030

Beijing has set 17 milestones targeting BCI breakthroughs by 2027 and a fully competitive industry by 2030; clinical implants and rapid market growth are accelerating investment and policy choices. Related: "Rapid Growth on State Backing" China’s BCI Industry Closes In on Neuralink Amid Regulatory Drag"

-

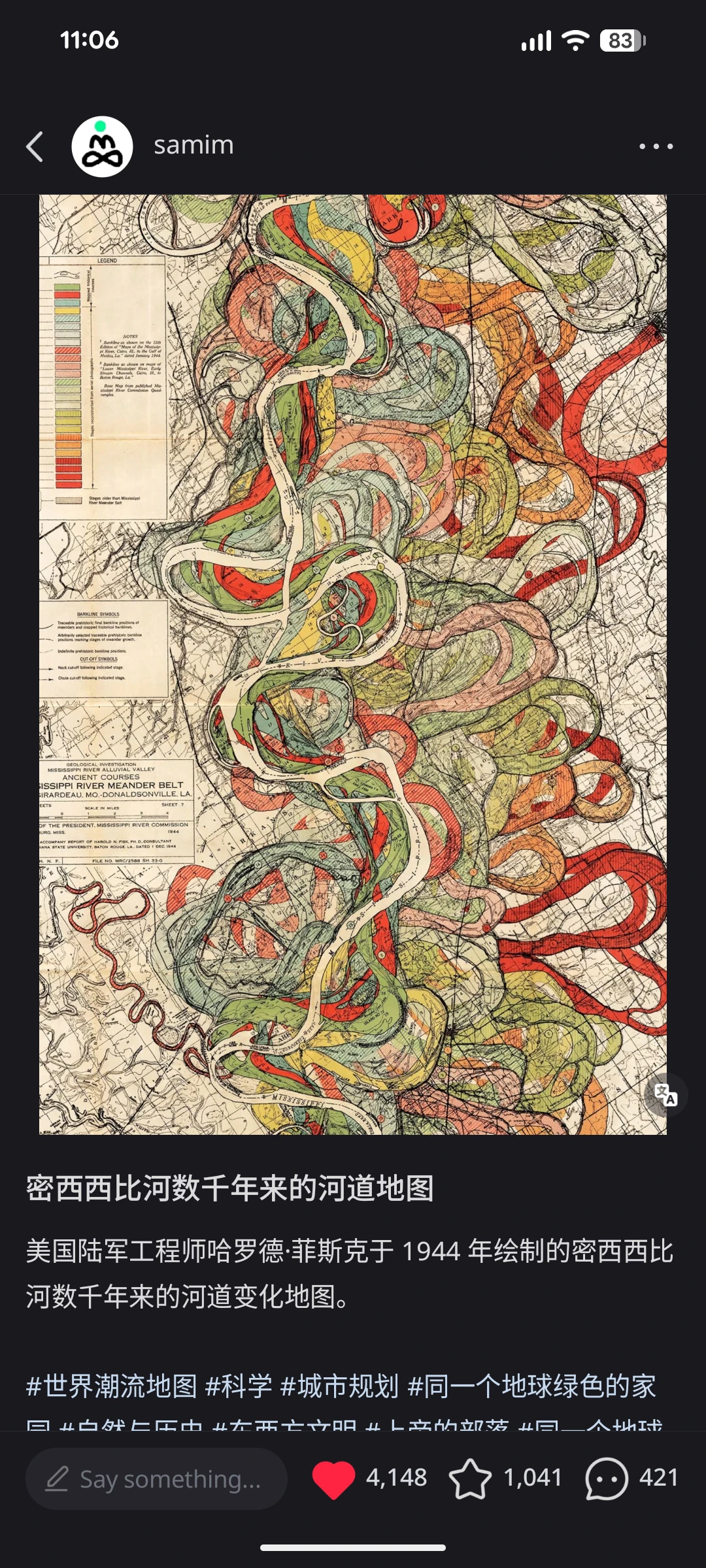

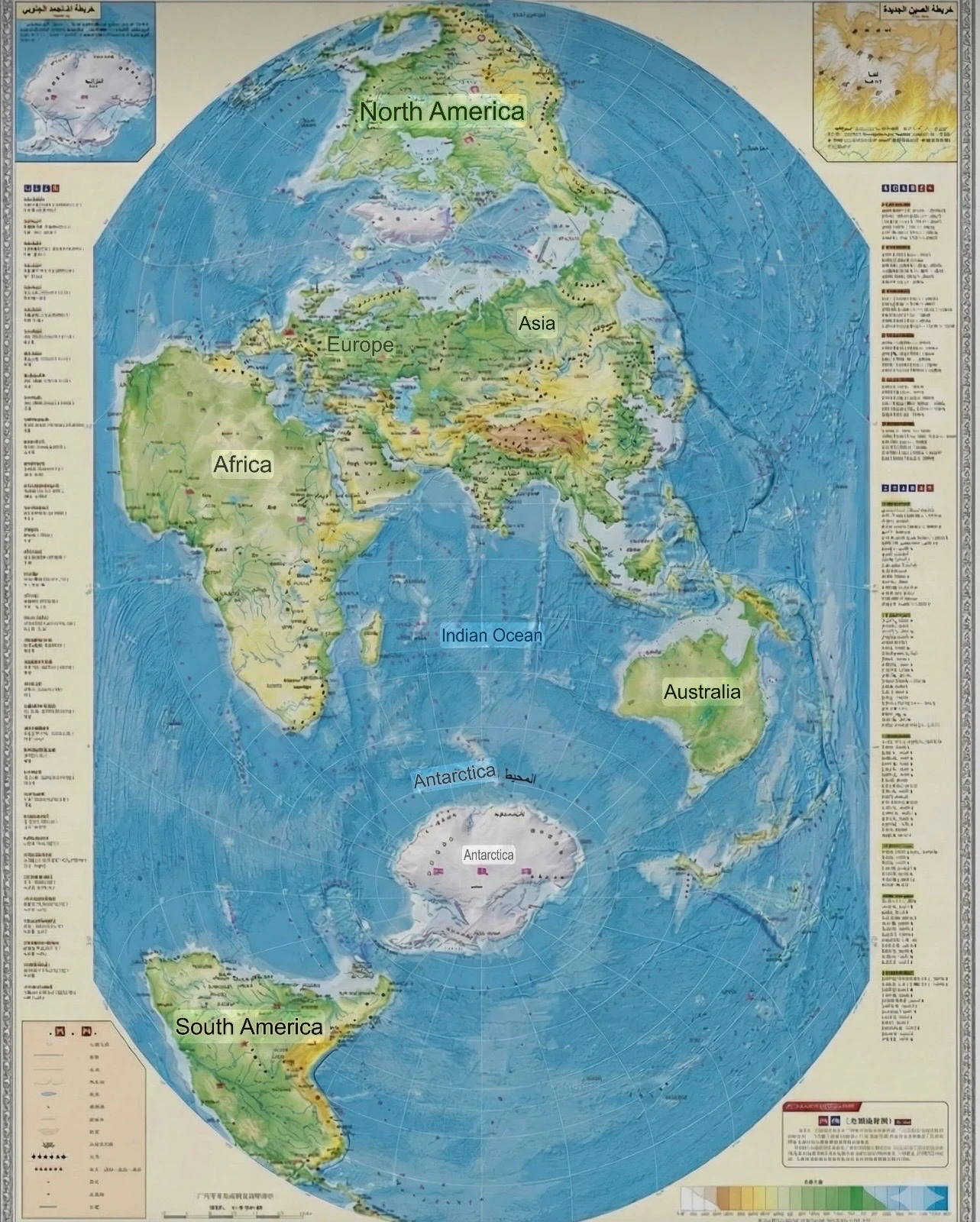

China is using this map in its schools

This isn't just an ordinary school map, nor is it an innocent attempt to alter a geographical projection. What we're using in our schools is a map of consciousness before it's a map of the land. It's a tool for rearranging how the Chinese generation sees the world, who stands at its center, and who lives on its periphery.

The map doesn't start at the Atlantic, as the world has for centuries, nor does it give Europe or the United States the visual center of gravity. The center here is distinctly Asian, with China at the natural heart of the scene, while Europe is pushed westward, and the Americas are relegated to the margins, as if they were distant geographical extensions rather than a cosmic axis.