Sir Basil Zaharoff: The Mystery Man of Europe Who Sold Both Sides

There was once a man who sold submarines to Greece and Turkey simultaneously — faulty ones, to both. He then bought Monaco. He helped birth what would become British Petroleum. Occultists claimed he was the reincarnation of an immortal alchemist. Anton LaVey dedicated The Satanic Bible to him. When he died in 1936, the financial architecture he moved through was just crystallizing into something permanent.

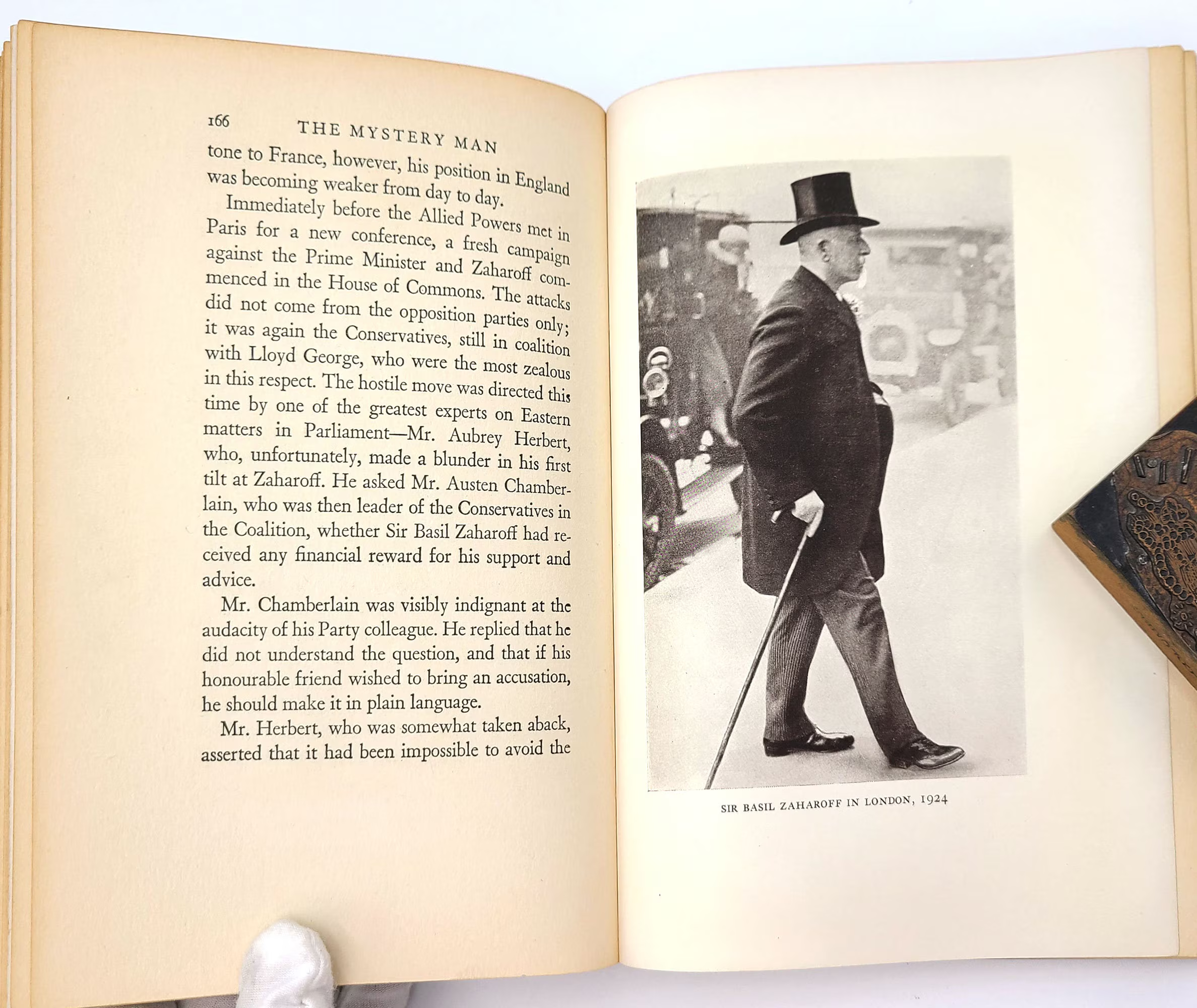

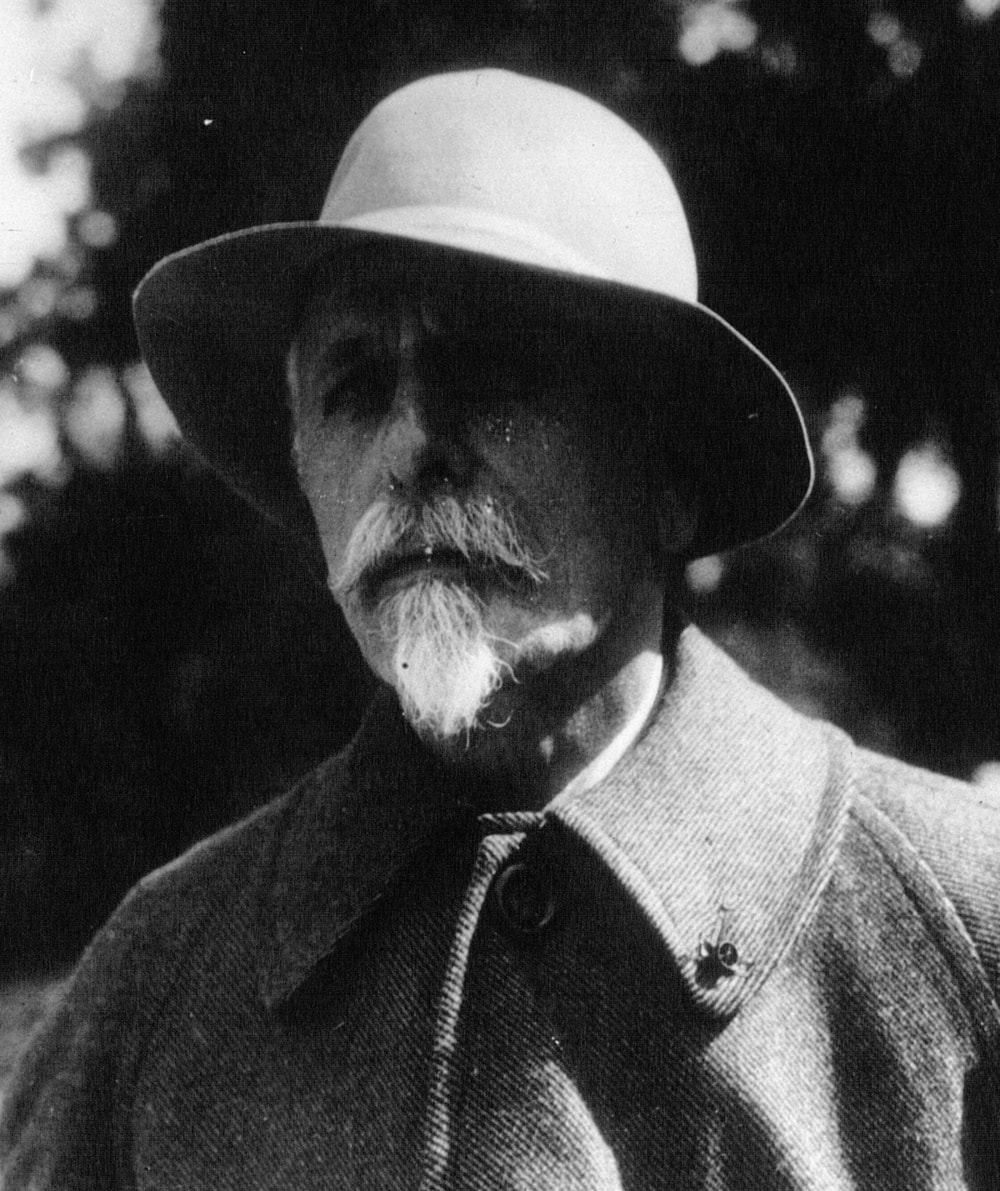

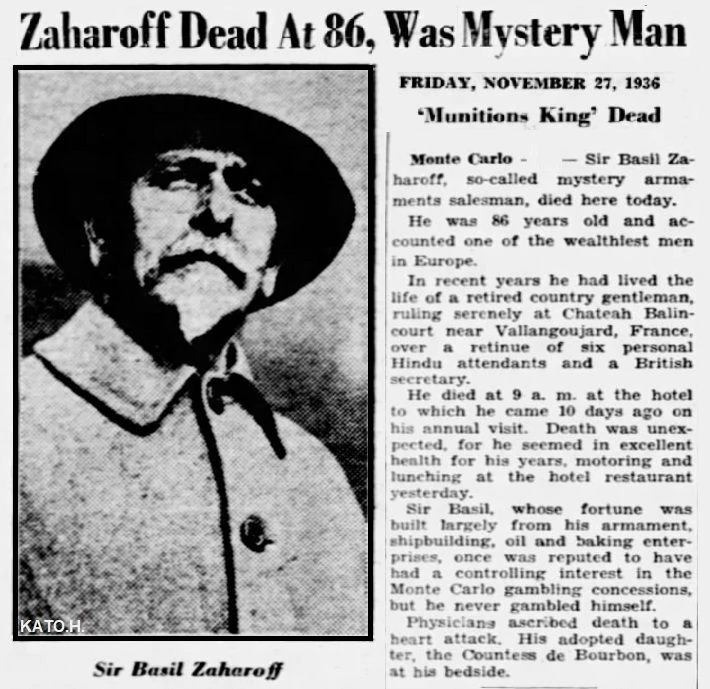

His name was Sir Basil Zaharoff, GCB, GBE — born Vasileios Zacharias (Βασίλειος Ζαχαρίας Ζαχάρωφ) in the Ottoman Empire, 1849. One of the richest men in the world during his lifetime. Known to contemporaries as the "Merchant of Death" and the "Mystery Man of Europe."

The Merchant of Death

Born in 1849 in the Ottoman Empire to a Greek family, Zaharoff's first job was as a tour guide in Constantinople's Galata district. His second was as a firefighter — a profession that, in 19th-century Istanbul, meant salvaging treasures from burning buildings for wealthy clients. He spoke a dozen languages. He understood, early, that borders are suggestions and that those who move between them hold the cards.

By his thirties, he was the Balkan representative for Thorsten Nordenfelt's arms company. His signature move — later known as Système Zaharoff — was selling weapons to both sides of a conflict, sometimes delivering machinery he knew to be faulty. He didn't just profit from wars — he helped engineer them into existence.

The submarine deals are the purest example. First, he sold a steam-powered submarine to Greece. Then he went to the Turks and warned them: Greece now has a dangerous new weapon. Frightened, they bought two. Then he visited the Russians and explained that the Turks would soon control the Black Sea. They bought two more. Five submarines sold, all of them nearly useless. When the Ottomans tested theirs by launching a torpedo, the vessel capsized and sank.

His sabotage was as elegant as his salesmanship. When the American inventor Hiram Maxim developed a machine gun far superior to Nordenfelt's, Zaharoff sabotaged three consecutive public demonstrations: in La Spezia, he got Maxim's men so drunk the night before that they couldn't operate the gun; in Vienna, he tampered with the weapon mid-demo; at a third showing, he planted rumors that Maxim couldn't mass-produce. By 1888, Maxim had no choice but to merge with Nordenfelt — with Zaharoff taking a large commission and eventually becoming an equal partner. He bought his competition by breaking it first.

The Casino and the Oil

Zaharoff didn't just sell death. He bought pleasure. When Monaco's Société des Bains de Mer — the company that owns the Monte Carlo Casino — fell into debt, Zaharoff acquired it and revitalized it. The merchant of death became the landlord of Europe's most glamorous gambling den. The same hands that signed arms contracts now signed checks for the roulette tables.

And there's more. He was instrumental in the incorporation of a company that would become a predecessor to British Petroleum. Oil, the fuel of the 20th century's wars, was also his business. He understood what few did at the time: whoever controls the substrate — whether weapons, energy, or entertainment — controls the game.

The Monte Carlo Casino wasn't just a business. It was a meeting point for aristocrats, spies, and the strange fraternity of men who moved between visible power and its shadows. In that era, the line between the gambling table and the war room was thin. The same circles that frequented Monte Carlo also populated the lodges, the salons, and the secret societies of the age.

The Occultist's Muse

French esotericist René Guénon — one of the 20th century's most influential traditionalist thinkers — speculated that Zaharoff might be the modern incarnation of "Master Rakoczi," an earthly representative of the so-called "Unknown Superiors." In occult tradition, Master Rakoczi is identified with the Count of St. Germain — the legendary 18th-century figure who claimed to be centuries old, who appeared in the courts of Europe with seemingly impossible knowledge, and who vanished without a verified death.

Was Zaharoff the Count, returned? Guénon thought it possible.

Decades later, Anton LaVey — founder of the Church of Satan — dedicated his Satanic Bible to Zaharoff, honoring him as an embodiment of Machiavellian will-to-power. LaVey later named his grandson "Stanton Zaharoff" in tribute. The merchant of death had become a patron saint of the Left-Hand Path.

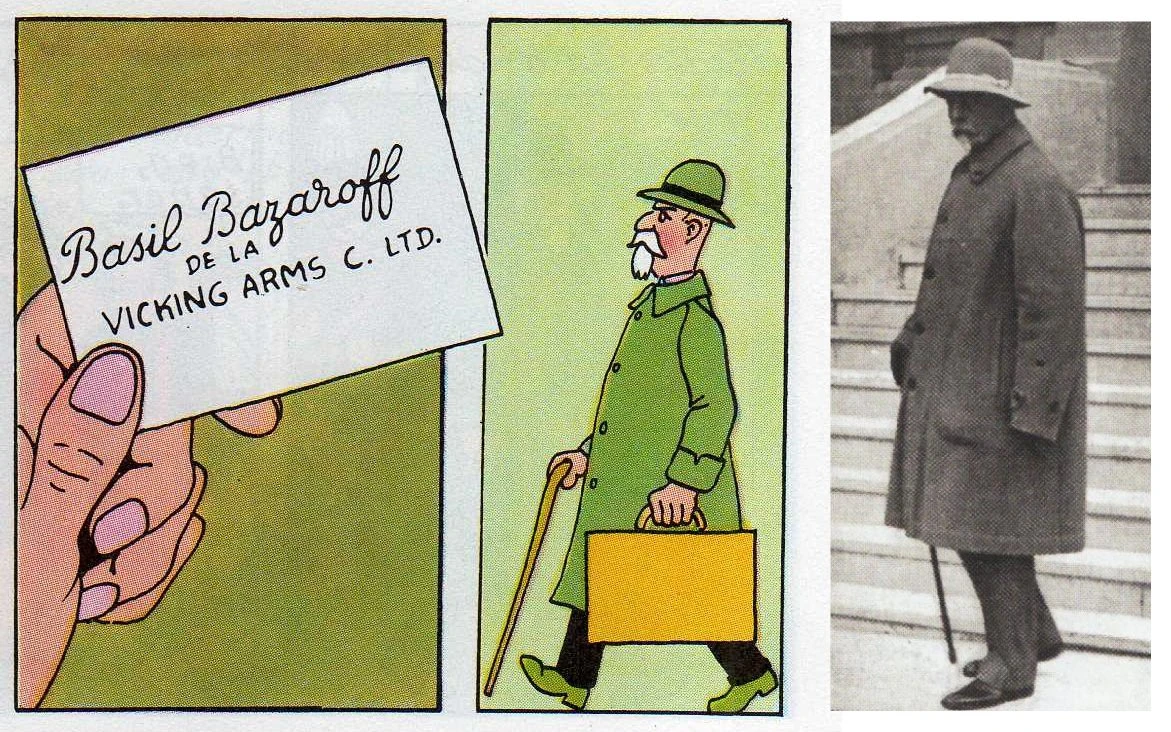

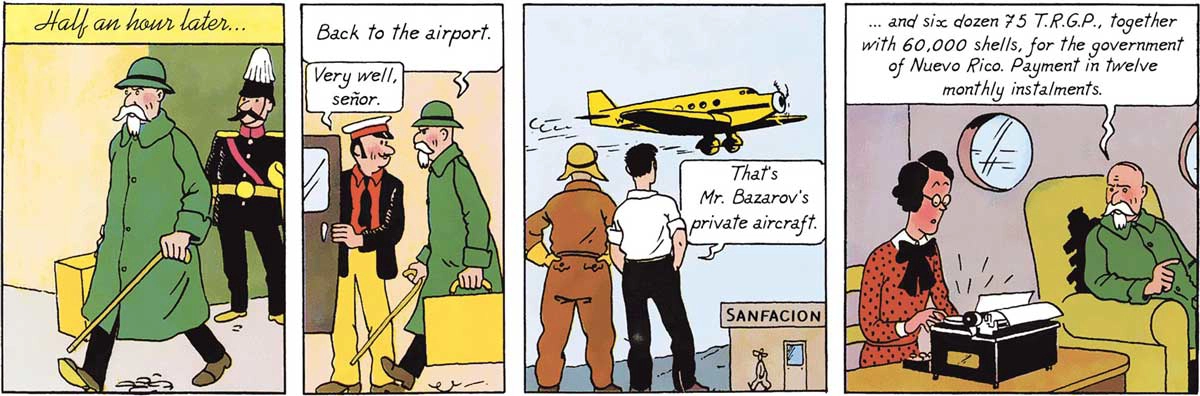

And the fiction writers saw it too. Eric Ambler modeled the sinister Dimitrios on Zaharoff in A Coffin for Dimitrios. George Bernard Shaw transmuted him into Andrew Undershaft in Major Barbara. Hergé put him in Tintin as the arms dealer Basil Bazaroff in The Broken Ear. He appears in Thomas Pynchon's Against the Day and Ezra Pound's Cantos (as "Metevsky"). Even the James Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld — the bald mastermind of SPECTRE — is believed to owe his lineage to the Mystery Man of Europe.

The Hidden Empire

Zaharoff died in 1936, in Monte Carlo, in the casino principality he had rescued from bankruptcy. But the architecture of invisible power he moved through was just being formalized.

Six years before his death, a peculiar institution had been founded in Basel, Switzerland: the Bank for International Settlements — the "central bank of central banks." It would survive two world wars, operate during Nazi occupation, and emerge as the quiet backbone of global finance. A tower in Basel where the world's central bankers meet in private, beyond the reach of any single nation. The networks Zaharoff had navigated — arms manufacturers, oil companies, sovereign wealth, intelligence services — were crystallizing into permanent infrastructure.

And not just the visible networks. The same years that saw the BIS founded also saw the proliferation of Egyptian Rites, Martinist lodges, and neo-Templar orders across Europe. Theodor Reuss was passing the torch of the O.T.O. The visible and invisible worlds were both reorganizing after the Great War. Zaharoff had operated in both. Now both were institutionalizing.

Fast forward ninety years. Switzerland still hosts the nerve center — Glencore, Vitol, Nestlé, Novartis — all interlocked with the same capital blocs and banking networks that trace back to that 1930 tower.

Empires don't fail — they transform. The Roman Empire became a church. The British Empire became a bank. The American Empire became the internet. The power structures Zaharoff navigated didn't disappear when borders were redrawn or wars ended. They shape-shifted. They went underground. They became infrastructure. He wasn't an anomaly. He was a prototype.

The Epistemic Firewall

So why does this all feel fantastical when you first hear it? Why does the thread from a Greek arms dealer to Swiss commodity giants to esoteric lodges to Basel banking towers sound like fiction?

Because the best-kept secrets don't need guards. They're protected by something more powerful: public incredulity. As someone once noted — the attribution is disputed — "Only puny secrets need protection. Big discoveries are protected by public incredulity."

The grand secrets persist not through suppression of evidence, but through the contamination of epistemology itself. You don't hide the truth — you make belief in it structurally impossible.

The Deeper You Look

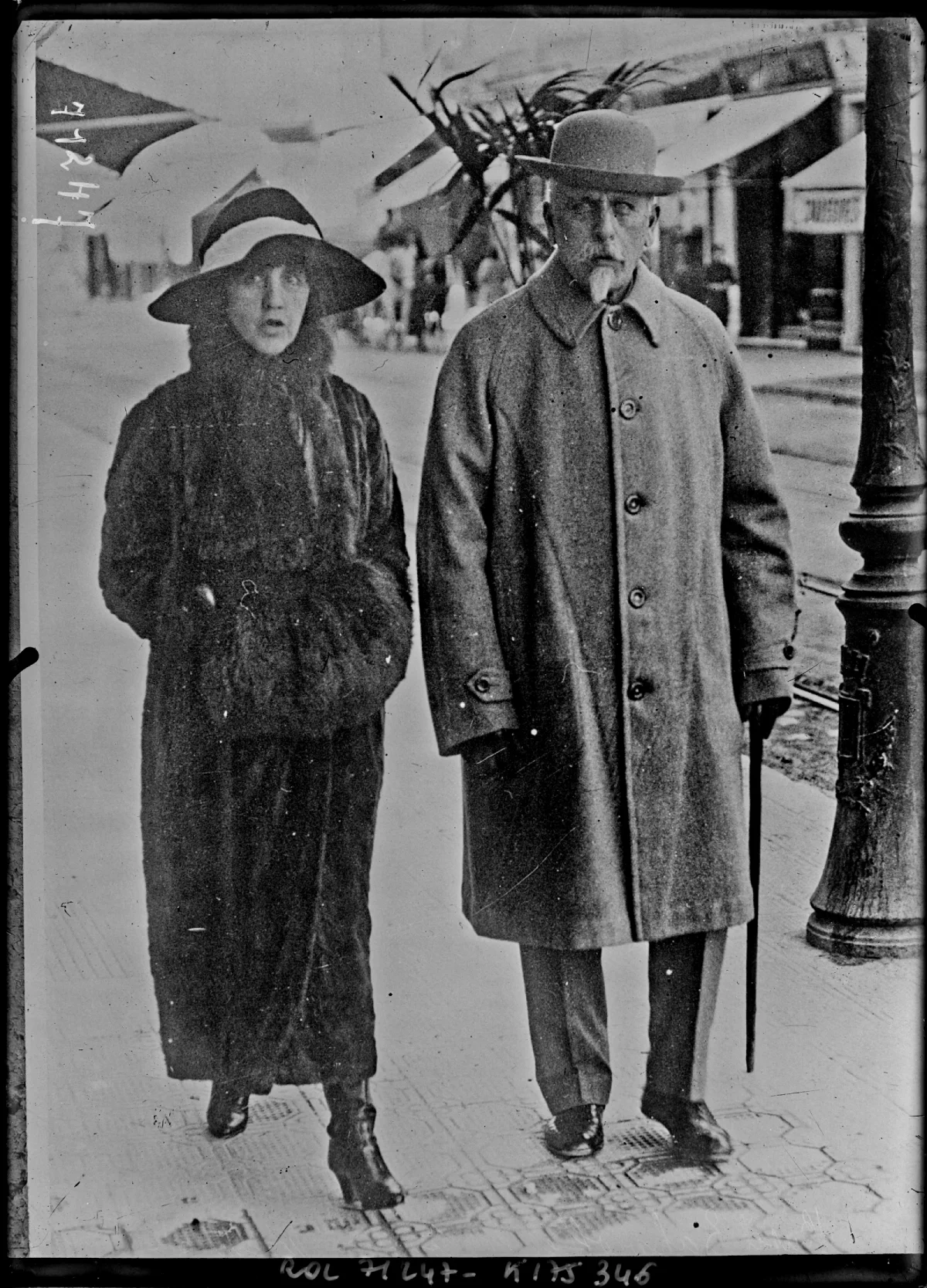

The record does not simplify. He was a bigamist — married Emily Burrows in England, then Jeannie Billings in New York for her inheritance. When exposed, he fled. He called himself Count Zaharoff and, later, Prince Zacharias Basileus Zacharoff. In 1883, in Galway, he lured young Irish women onto ships with promises of factory work in Massachusetts. He seduced María del Pilar, Duchess de Villafranca de los Caballeros, cousin to the King of Spain, and married her after her husband's death. He cultivated the prima ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska to access the Czarist court. He once attempted to bribe the entire Ottoman Empire with £10 million in gold to defect from Germany. By 1911, he sat on the board of Vickers. During the First World War, the company produced 4 battleships, 53 submarines, 2,400 cannons, and 120,000 machine guns. He was close friends with British Prime Minister Lloyd George and Greek Prime Minister Venizelos. He was knighted twice.

The more you learn, the less he resolves into a single story. He remains, as he was in life, the Mystery Man of Europe. There exists, supposedly, a pamphlet in the Bibliothèque nationale attributed to "Z.Z." and dated 1923, which claims the Count of St. Germain legend was itself a cover story — manufactured by the arms trade to provide deniability for men who could not be seen to exist. The pamphlet has never been authenticated. Its catalog number is 616.936.

Coda

In 1927, nine years before his death, Zaharoff burned all his papers and diaries. When his will was read, it listed assets of only £193,000 — a fraction of the fortune he had claimed. Where did the billions go?

The structures are still running. If you have read this far, you are already inside them.

Related