tag > Qi

-

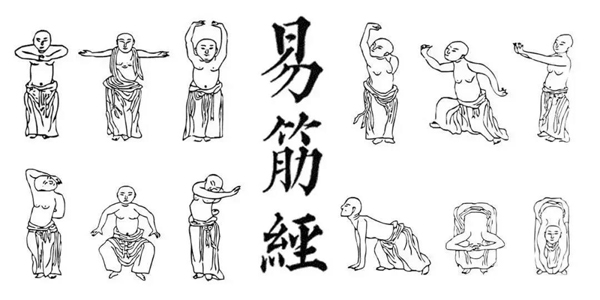

Santi Shi or Trinity pile standing is the most important and fundamental training in Xingyi Quan practice. It is saidthat “Santi Shi is the source of all skills.” In traditional training, beginners need to learn Santi Shi and practice itfor a long time before they can be taught other skills. Practicing Santi Shi can help practitioners improve theirmovements and the integration of internal and external components. Stability and rooting can also be increasedby this practice, as can relaxation and the control and use of shen, yi, qi and jin. Santi Shi training is emphasizedin every Xingyi Quan group and will be presented here as a foundation training for martial arts fighting skills.

-

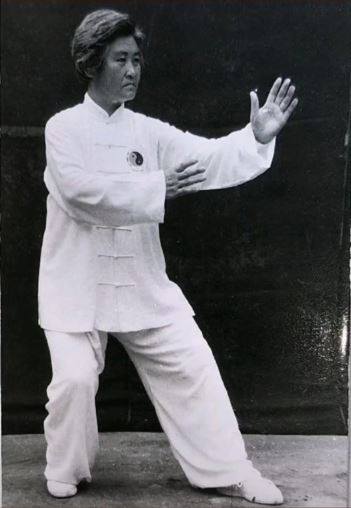

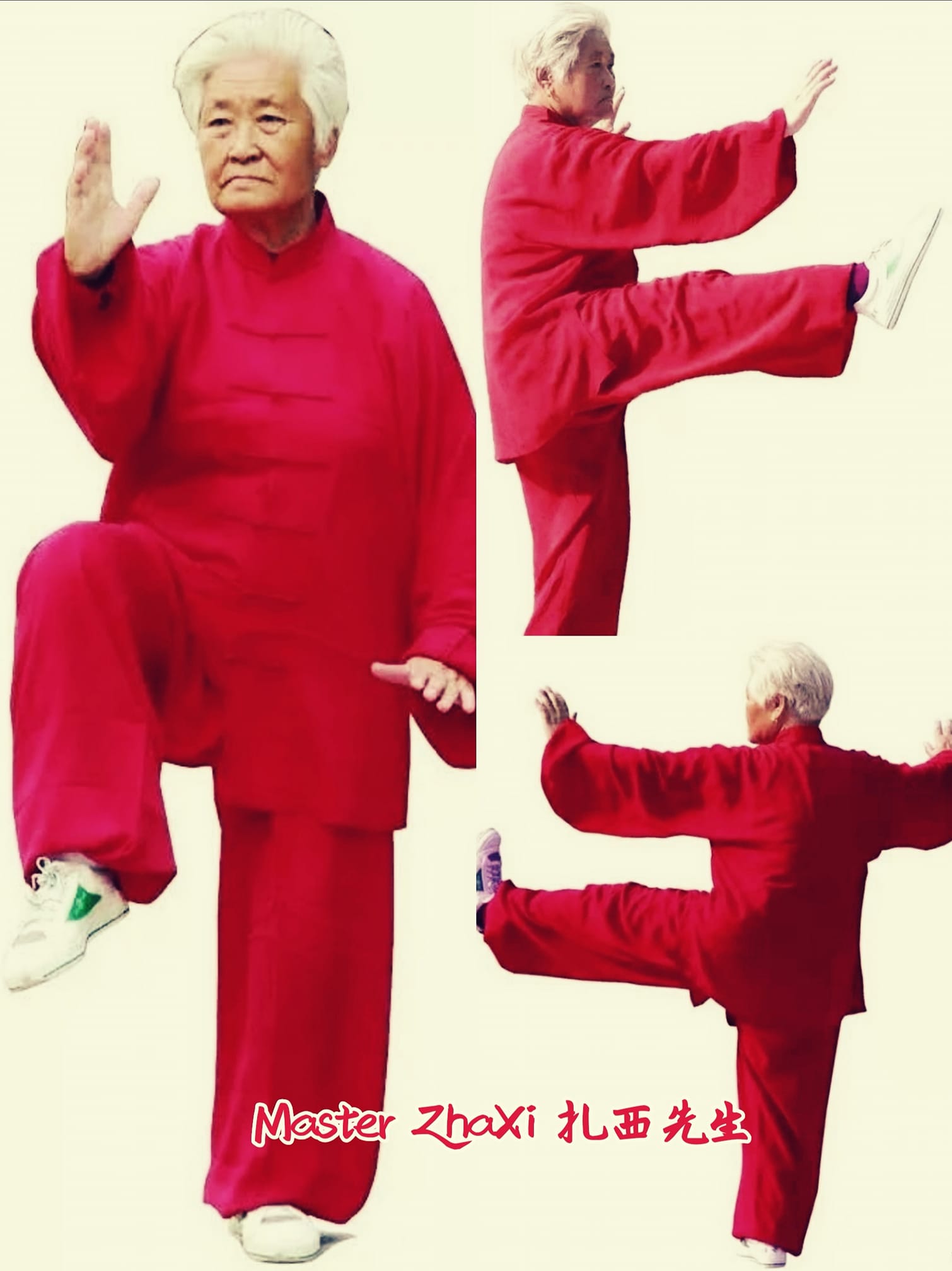

Master Zha Xi (i扎西)

"In 1970, at 38-year-old the Zhaxi suffered from a lung cancer and had to took away part of her right lung and three ribs. In the early days, she used the crutches to go to park to learn Taijiquan from her master ZhaoBin every day... However, with her strong will and perseverance, Zhaxi gradually stopped using the walking stick and became stronger. She remembered that the doctor said she would probably live for more 5-10 years, but she believed Taijiquan let her live for almost more 50 years."

Longer Version: The Tai Chi Pioneer Who Fought Illness with Grace and Grit

Born in 1932 in Qinghai, Master Zhaxi was a fifth-generation Yang Style Tai Chi inheritor, a seventh-degree martial arts master, and president of the Xianyang Yongnian Tai Chi Association. But her legacy didn’t begin with titles — it began with survival.

In the 1960s, while working in Tibet, Zhaxi developed severe rheumatoid arthritis, followed by lung cancer. At 38, she had two lobes of her right lung removed, and the last lobe later failed. After surgery, doctors quietly warned her husband: "She might live five years—ten at most."

After years of failed treatments, she gave up on medicine—and picked up a cane. At her lowest point, Zhaxi discovered Tai Chi., when by chance, she met Zhao Bin, a grandson of the famous Tai Chi Master Yang Chengfu. Encouraged by Mr. Zhao Bin and holding a glimmer of hope for life, Zhaxi began her Tai Chi journey. To her surprise, as she persisted in practicing every day, her body did slowly change. After studying for about half a year, Zhaxi said goodbye to the medicine bottle and her body became stronger!

Her recovery has become a symbol of Tai Chi’s healing power. In 1978, at the instruction of her teacher, Zhaxi officially set up a place to teach Tai Chi at the gate of Xi'an Zoo. In 1986, she won silver at China’s first national Tai Chi Sword Competition. Since then, she’s taught over 10,000 students, founded the Xianyang Yongnian Tai Chi Association (now with 2,000+ members and 30+ coaching centers), and earned nearly 200 medals in national competitions!

She even returned to Tibet to set up a Tai Chi academy, where she was twice honored for her work in aging and national unity. Her story has been featured on CCTV, and she published books and instructional videos to pass down her art.

Master Zhaxi passed away on January 3, 2019, at the age of 88. Her legacy lives on in the thousands she taught, the strength she embodied, and the timeless art she helped preserve.

She was living proof that Tai Chi is NOT just movement — It’s Medicine, Mindset, and a Way Back to Life!

-

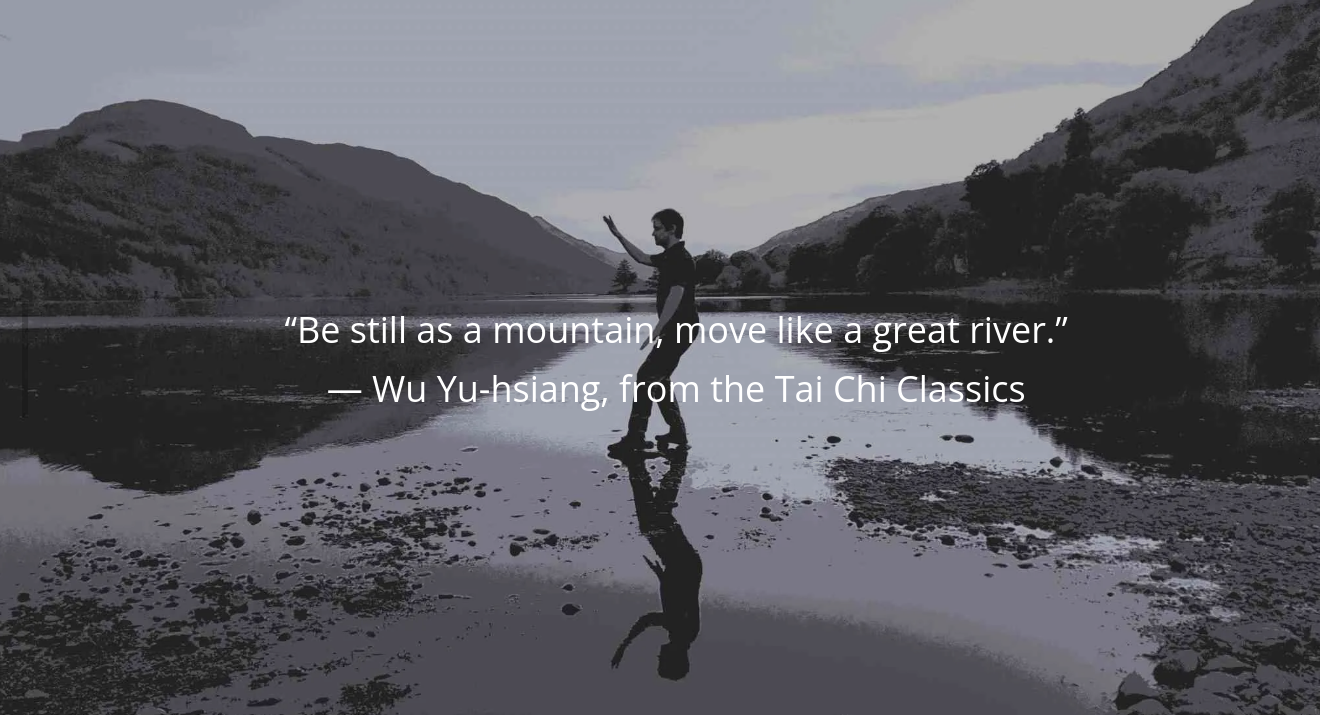

“Be still as a mountain, move like a great river.” — Wu Yu-hsiang, from the Tai Chi Classics

EXPOSITIONS OF INSIGHTS INTO THE PRACTICE OF THE THIRTEEN POSTURES

by Wu Yu-hsiang (Wu Yuxian) (1812 - 1880) sometimes attributed to Wang Chung-yueh as researched by Lee N. Scheele

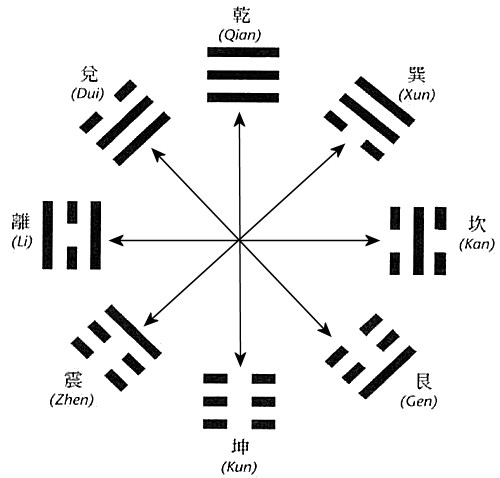

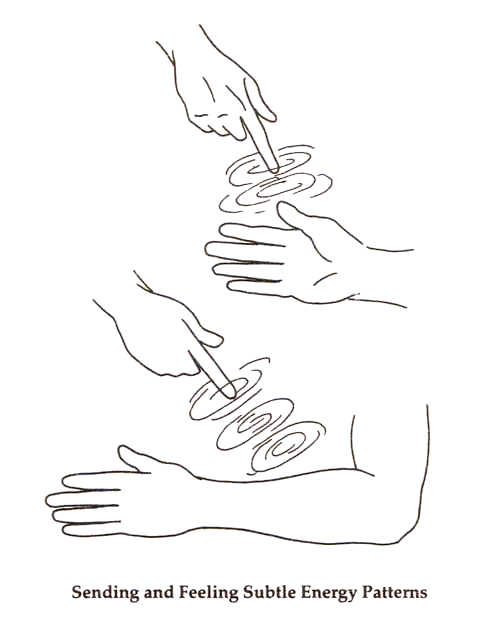

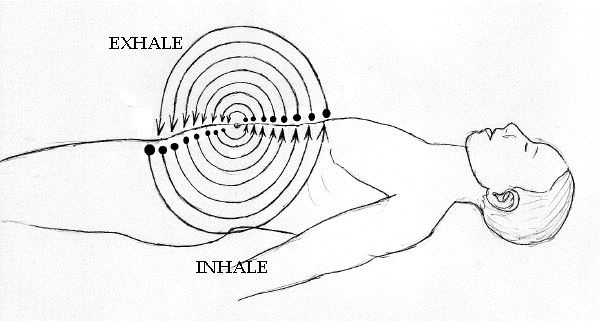

The hsin [mind-and-heart] mobilizes the ch'i [vital life energy]. Make the ch'i sink calmly; then the ch'i gathers and permeates the bones. The ch'i mobilizes the body. Make it move smoothly, so that it may easily follows the hsin.

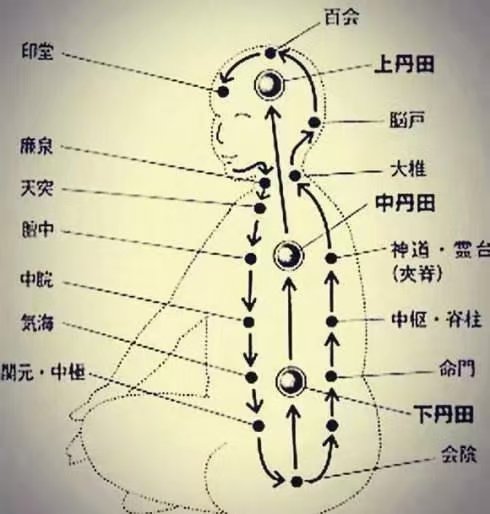

The I [mind-intention] and ch'i must interchange agilely, then there is an excellence of roundness and smoothness. This is called "the interplay of insubstantial and substantial." The hsin is the commander, the ch'i the flag, and the waist the banner. The waist is like the axle and the ch'i is like the wheel.

The ch'i is always nurtured without harm. Let the ch'i move as in a pearl with nine passages without breaks so that there is no part it cannot reach.

In moving the ch'i sticks to the back and permeates the spine.

It is said "first in the hsin, then in the body." The abdomen relaxes, then the ch'i sinks into the bones. The shen [spirit of vitality] is relaxed and the body calm.

The shen is always in the hsin. Being able to breathe properly leads to agility.

The softest will then become the strongest. When the ching shen is raised, there is no fault of stagnancy and heaviness. This is called suspending the headtop. Inwardly make the shen firm, and outwardly exhibit calmness and peace.

Throughout the body, the I relies on the shen, not on the ch'i. If it relied on the ch'i, it would become stagnant. If there is ch'i, there is no li [external strength]. If there is no ch'i, there is pure steel. The chin [intrinsic strength] is sung [relaxed], but not sung; it is capable of great extension, but is not extended. The chin is broken, but the I is not. The chin is stored (having a surplus) by means of the curved. The li* is released by the back, and the steps follow the changes of the body. The mobilization of the chin is like refining steel a hundred times over. There is nothing hard it cannot destroy. Store up the chin like drawing a bow. Mobilize the chin like drawing silk from a cocoon.

Release the chin like releasing the arrow.

To fa-chin [discharge energy], sink, relax completely, and aim in one direction! In the curve seek the straight, store, then release. Be still as a mountain, move like a great river. The upright body must be stable and comfortable to be able to sustain an attack from any of the eight directions. Walk like a cat. Remember, when moving, there is no place that does not move. When still, there is no place that is not still. First seek extension, then contraction; then it can be fine and subtle. It is said if the opponent does not move, then I do not move. At the opponent's slightest move, I move first."

To withdraw is then to release, to release it is necessary to withdraw. In discontinuity there is still continuity. In advancing and returning there must be folding. Going forward and back there must be changes.

The form is like that of a falcon about to seize a rabbit, and the shen is like that of a cat about to catch a rat.

* Scholars argue persuasively that the use of the word li here is a mistranscription and the passage should read chin.

-

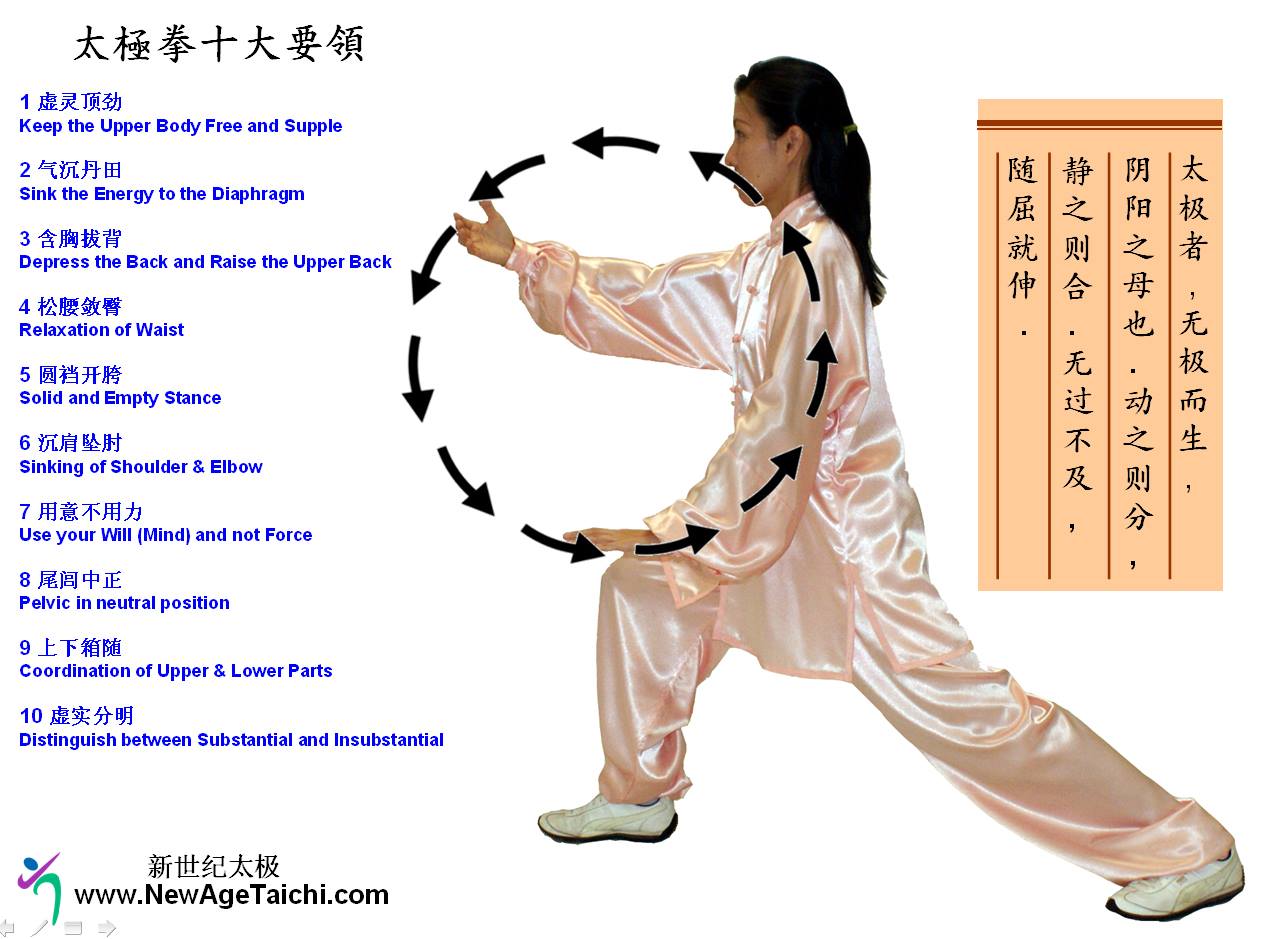

虛靈頂勁 (“Xu ling ding jin” — “the crown of the head as if suspended”)

- 1 虚灵顶劲 Keep the Upper Body Free and Supple

- 2 气沉丹田 Sink the Energy to the Diaphragm

- 3 含胸拔背 Depress the Back and Raise the Upper Back

- 4 松腰敛臀 Relaxation of Waist

- 5 圆裆开胯 Solid and Empty Stance

- 6 沉肩坠肘 Sinking of Shoulder & Elbow

- 7 用意不用力 Use your Will (Mind) and not Force

- 8 尾闾中正 Pelvic in neutral position

- 9 上下相随 Coordination of Upper & Lower Parts

- 10 虚实分明 Distinguish between Substantial and Insubstantial

-

Zhan Zhuang

Zhan Zhuang (which means "standing pole" or "standing like a pole") is not a passive relaxation exercise, but a dynamic and incredibly complex standing meditation practice. It's not about "doing nothing," but "doing everything" at a deep internal level.

From the very beginning, the student must study and master fundamental concepts that many schools don't understand:

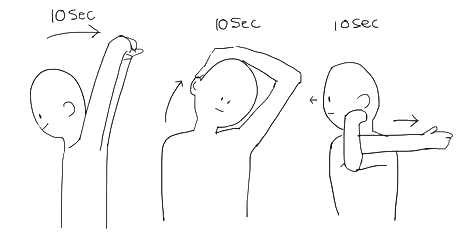

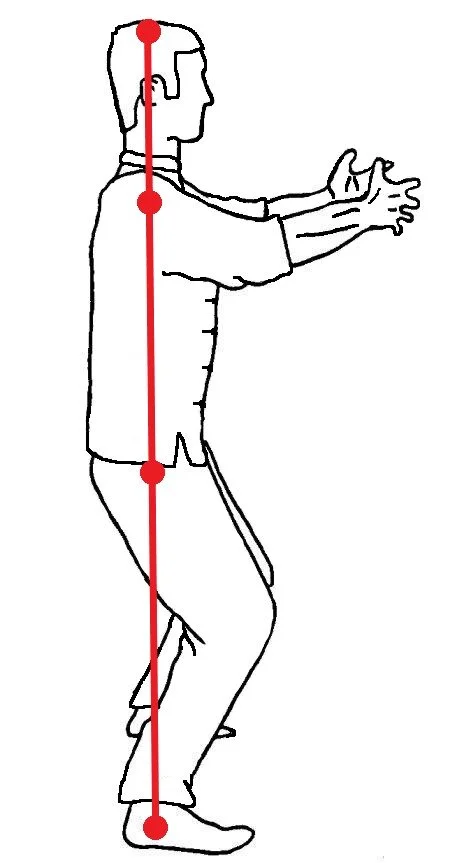

1-The first phase is the meticulous study of posture. The instructor guides the student to find the exact position of the body, from head to toe. This includes aligning the spine, adjusting the pelvis, positioning the knees, and precisely distributing the weight. It's not a natural posture; it's an engineered construction that must be learned.

2- Relaxation (Song): One of the first and most difficult tasks is learning to release unnecessary muscular tension. This doesn't happen automatically. The practitioner must "study" their body, identify blockages, and learn to consciously release tension. It's an active mental and physical effort.

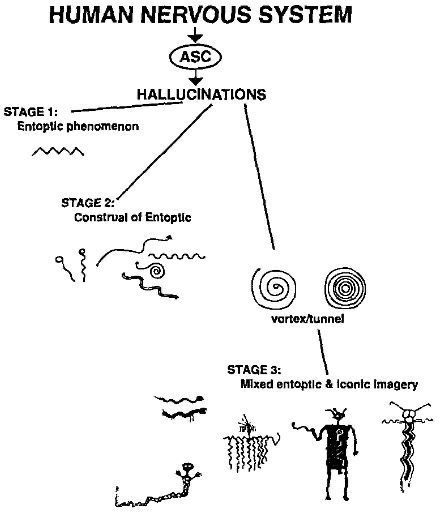

3- Mental Intention (Yi): This is the heart of the practice and what makes it a "study" from the outset. You learn to use your mind to perceive and guide internal sensations, such as the "feeling of a ball in your arms" or the "flow of energy." External stillness hides intense internal activity.

-

Life Goals

When asked, "What is your life's goal?" most people point to external achievements—fame, wealth, or groundbreaking innovations. But life is fleeting. In the blink of an eye, we and everyone we love will be gone.

Through my own journey, I’ve come to realize that the most meaningful goal isn’t something external, but internal: to be fully present in each moment. To truly connect—with ourselves and others. To radiate unconditional love, extend compassion to all things, and be deeply at ease.

May our practice and life be of benefit to all beings everywhere.