tag > Essay

-

The Forger's Dilemma: On Memory That Cannot Be Faked

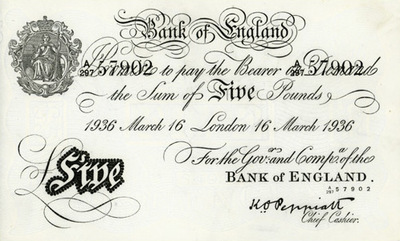

In 1942, the Nazis launched Operation Bernhard, a scheme to forge British banknotes so perfectly that dropping them over England would collapse the economy. They succeeded technically. The forgeries were immaculate. But the plan failed. Why?

Because money isn't paper. Money is memory: distributed memory, held in millions of minds, woven into habits and expectations. You can print a perfect note, but you cannot print the web of trust that gives it meaning. The forgery was flawless. What it forged was hollow.

This is the forger's dilemma: the more distributed a system of meaning, the harder it is to counterfeit. A single ledger can be altered. A network remembers.

How deep does this go?

The Paradox of Holographic Memory

All the way down.

Information security in decentralized holographic memory networks is paradoxical.

In a holographic system, every part contains the whole. Cut a hologram in half, and each half still shows the complete image. This makes it resilient. You cannot destroy the memory by attacking any single node. But it also makes it impossible to secure in the traditional sense. How do you lock a door that is everywhere?

The paradox: maximum distribution means maximum persistence but minimum control. What cannot be erased also cannot be owned. This sounds like a technical problem. It's actually a description of life.

The Queen in Through the Looking-Glass tells Alice: "It's a poor sort of memory that only works backwards." We laugh, but she's right. Linear memory, the kind that only recalls the past, is the impoverished version. The kind forgers understand. Real memory is stranger: it loops, it anticipates, it contains itself.

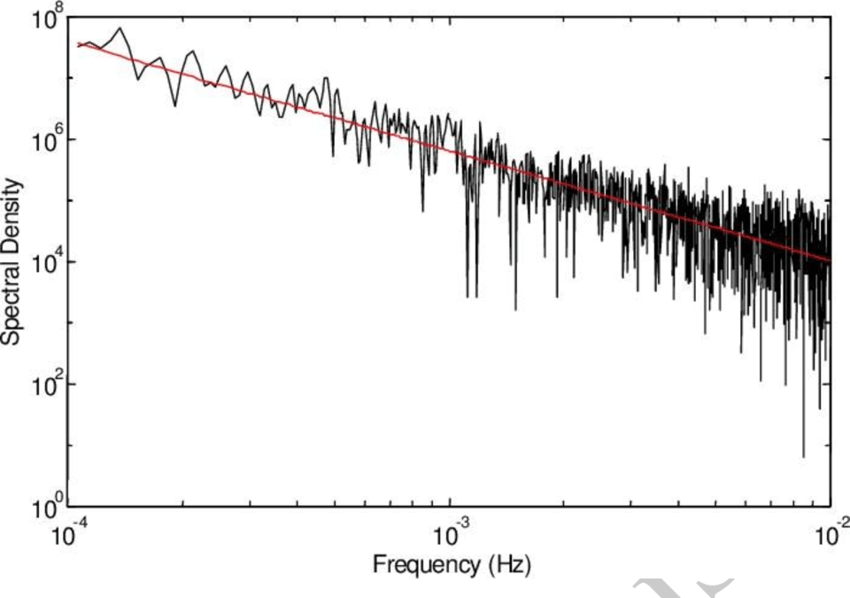

There's a pattern that shows up everywhere distributed memory lives: 1/f noise, also called pink noise. It appears in brain dynamics, heartbeats, river flows, stock markets, music. The power decreases as frequency increases, but never disappears. It's the signature of systems at the edge, what Per Bak called self-organized criticality. Mandelbrot mapped these patterns his whole life: fractals, self-affinity, globality. The same structure at every scale.

This is the sound of memory at the edge of chaos. Systems that exhibit 1/f noise remember across all timescales simultaneously: short bursts nested inside longer rhythms nested inside longer still. A forgery is flat: one scale, one moment. Real memory is fractal.

Any system capable of self-reference and rich structure will exhibit: scale invariance, persistent incompleteness, distributed paradox, no final temporal closure.

Trying to "solve" incompleteness is like trying to flatten a fractal. You can't. You can only design with it.

Evolution Is Cleverer Than You Are

Leslie Orgel, one of the founders of origin-of-life research, left us with his Second Rule: "Evolution is cleverer than you are."

This isn't humility. It's an observation about distributed memory. Evolution has been running experiments for 4 billion years, in parallel, across every niche on Earth. Every solution it finds is written into the living record, encoded not in any central archive, but in the bodies, behaviors, and biochemistry of every organism.

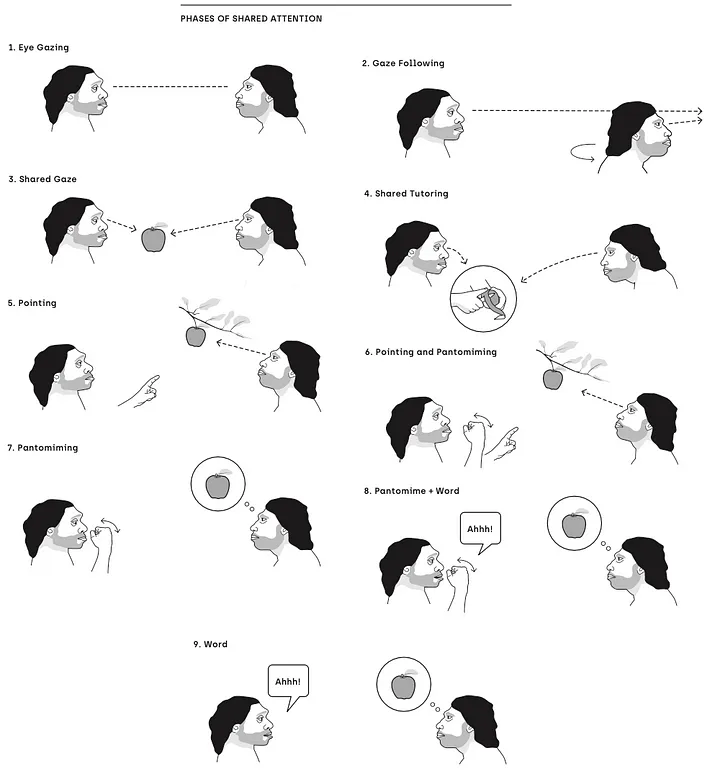

You cannot forge this. You can sequence a genome, but the meaning of that genome is held in the relationships it implies: the shared attention loops between predator and prey, the molecular handshakes between symbiont and host, the layered memory of every extinction and adaptation. Language itself emerged this way, not from one genius, but from minds looking at the same thing and recognizing that they are looking at the same thing. Meaning bootstrapped itself through mutual gaze.

Which raises a question that haunted Max Delbrück, Nobel laureate and founder of molecular biology: if life is information, but information that does something, a pattern that persists by actively maintaining itself, then what kind of thing is it? Neither mechanism nor mystery. Not quite matter, not quite idea. Delbrück suspected life would reveal a paradox akin to wave-particle duality in physics. Something that dissolves the distinction.

Memory with agency. Memory that responds, adapts, resists erasure. The forger's nightmare.

Intelligence at Every Scale

Scale up.

The belief that intelligence is exclusive to a specific level of complexity (animals/humans) is absurd. Consider the possibility of unconventional computation occurring on the scale of planets and galaxies. What other forms of collective, super-intelligent life are we overlooking?

If memory is distributed, and distributed memory cannot be faked or simulated, what does it mean that the universe is full of distributed systems? (This, incidentally, is why simulation theory feels shallow. A simulation is a forgery. And we've already established what happens to forgeries.) Galaxies have been processing information for 13 billion years. What do they remember? What are they computing?

We assume cognition requires brains. But brains are just one solution. Ant colonies think without any individual ant understanding the whole. Markets process information no trader fully grasps. Perhaps planets dream in ways we cannot recognize: geologic memory, climatic memory, the slow thought of tectonic plates.

Places That Remember

But you don't need to scale up to galaxies. Memory architecture exists at human scale too.

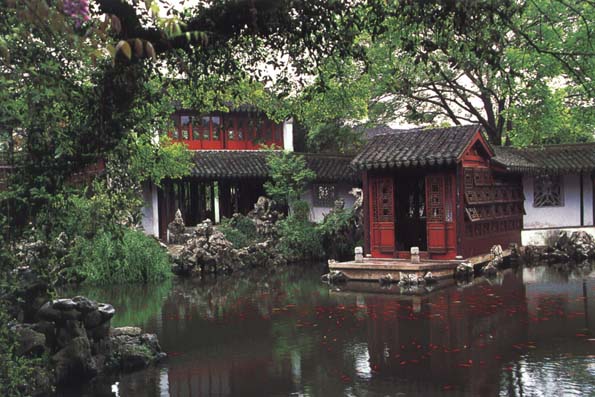

In Suzhou, there is a garden called The Retreat and Reflection Garden. Built in 1885 for a disgraced official who hoped to remedy his wrongdoings through contemplation. Water forms the center. Buildings float at the edge. Gardens within gardens. Every sightline triggers associations. Every pool reflects what it cannot contain.

This is not decoration. This is technology: memory architecture. The official walks through designed experience, and in walking, is changed. Yuan Long spent two years building it. It has been remembering for 140.

Or consider the slime mold. A single-celled organism with no brain, no nervous system. Yet it remembers. Researchers found that memory about nutrient location is encoded in the morphology of its network: the thickness of its tubes, the patterns of its growth. The slime mold's body is its memory. No central archive. No separation between the map and the territory.

And now we're building crystals that do the same. 5D memory crystals can preserve human DNA for billions of years. Not digital storage that degrades, but physical structure that outlasts planets. The garden remembers for centuries. The crystal remembers for eons. The slime mold remembers in its very flesh.

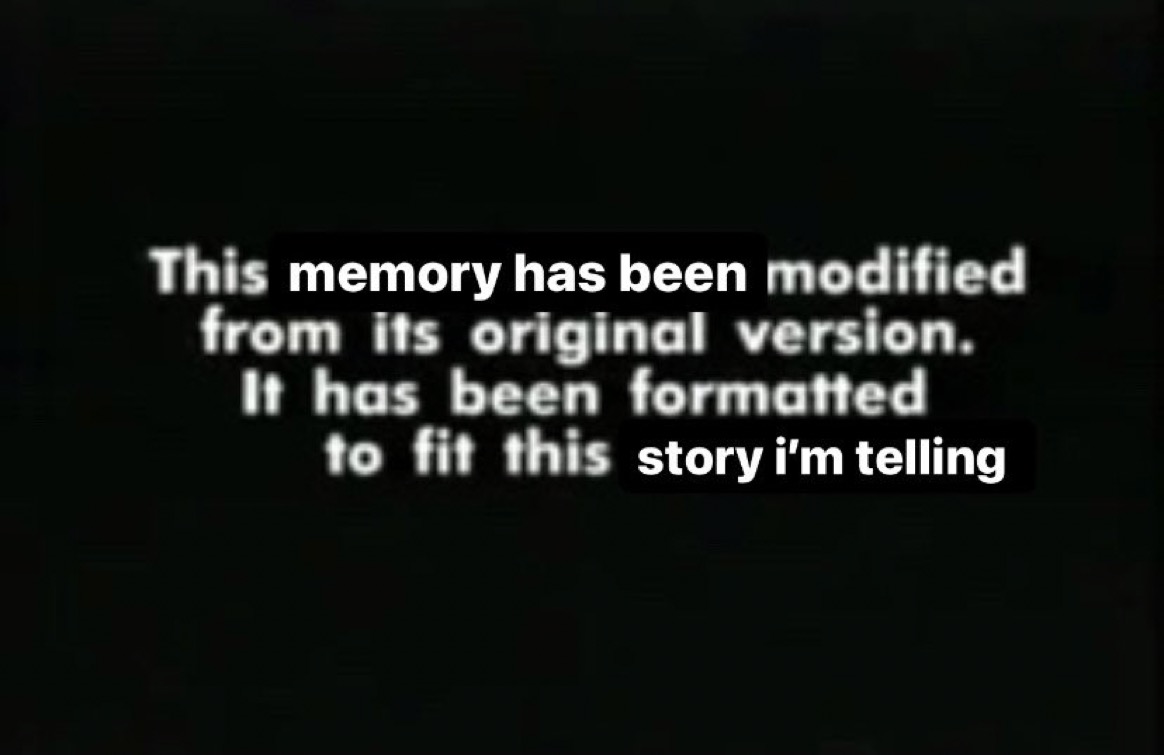

And yet: in Chinese mythology, Meng Po stands at the bridge between lives, serving a soup brewed from the tears of the living. Drink it, and your memory is erased for reincarnation. Even the cosmos needs forgetting. Memory that cannot let go becomes a prison. The garden is designed with empty spaces. The hologram requires interference. The forger's mistake wasn't just that he couldn't copy the memory. It was that he didn't understand: memory includes its own erasure.

Memento

So here's the secret the forgers never understood: You cannot fake what you are standing inside. Memory isn't stored. Memory is.

Consciousness. Language. The web of mutual recognition. The hum of 1/f noise in your own neurons as you read this sentence. You are the distributed memory. You are the fractal. You are the garden, remembering yourself. Memento.

#Philosophy #History #Biology #fnord #Paradox #Essay #Complexity

-

When the Forest Laughs: Consciousness, Boundaries, and the Wisdom of Flow

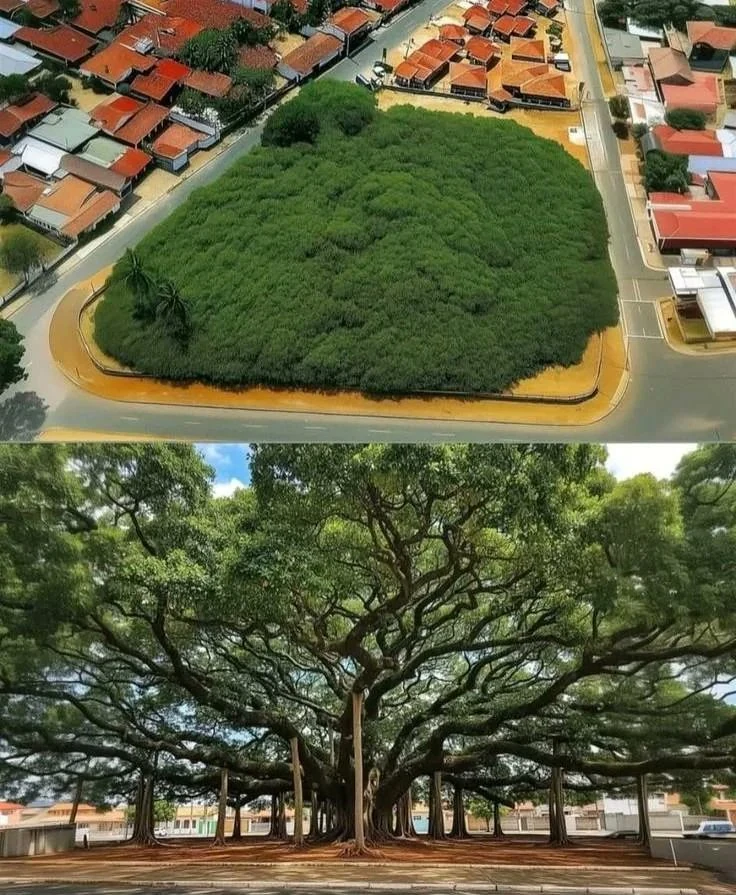

In Natal, Brazil, there is a forest that is actually one tree. The Pirangi cashew covers over 8,500 square meters—an entire city block—spreading outward through a genetic quirk: its branches droop, touch the red earth, and root again. From above, it looks like a forest. From inside, you walk through dappled shade, heat pressing your skin, the air thick with the sweet-rot smell of fallen cashew fruit, and you wonder whose canopy is whose. Whose roots drink from the same darkness? But it's all one organism. One tree that forgot where it ended.

I keep returning to this image when I think about consciousness. Not consciousness as a problem to be solved—the "hard problem," the neural correlates, the philosophical zombies—but consciousness as something we might be doing wrong by trying to pin it down at all.

John Donne knew this in 1624: "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main." The tree that is also a forest. The self that is also the world. We draw lines where nature draws none.

Hildegard von Bingen saw it eight centuries ago: the world as a cosmic egg, pulsing with viriditas—greenness, life-force, the wet fire that makes things grow. Everything connected to everything by this green flame.

The Comedy of Edges

Here's a proposal: What if every serious conference on consciousness was required to dedicate half its time to comedy? Not as intermission, but as method. I suspect we'd progress just as much in unraveling that great mystery as with purely serious scientific inquiry—and we'd have a far better time doing it.

Why comedy? Because laughter is what happens when a boundary dissolves unexpectedly. The setup creates a frame—this is what's happening—and the punchline shatters it. For a moment, we glimpse something larger than the story we were telling ourselves. The self that was bracing for one thing suddenly finds itself in another.

This is not so different from what contemplatives describe. The moment of insight. The crack in the container. The tree that discovers it's also the forest.

The Master Who Makes the Grass Green

Robert Anton Wilson liked to remind us of an old Hermetic insight: "You are the master who makes the grass green." The scientist is not separate from what the scientist observes. The perceiver shapes the perceived. No matter what reality tunnel you live in, the world will organize itself to be compatible with it.

The grass is green because you're making it green. The forest laughs because you're in on the joke.

Where Does the River End?

Around the world, there are strange sculptures called flowforms—vessels designed to make water spiral and dance as it passes through. Invented by John Wilkes, inspired by the rhythmic pulsing he observed in nature, they don't force the water into shape. They invite it.

The water enters, meets curved resistance, and begins to spiral—finding its own rhythm, its own memory of movement. Some claim this enlivens the water, restructures it. Whether or not you believe that, the metaphor is irresistible: flow finds form when you stop forcing.

Maybe consciousness is like this. Not a container with edges, but a current. Not a thing that starts here and ends there, but a movement that takes temporary shape—in this body, this moment, this thought—before spiraling onward.

We ask "where is consciousness located?" as if it were a marble in a skull. But ask instead: where does the river end? At the delta? The sea? The cloud that rises and returns as rain? The answer is: it doesn't. It only transforms.

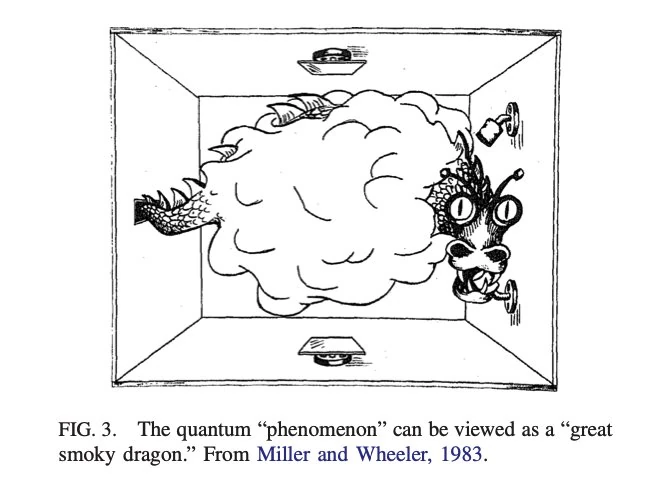

The Smoky Dragon

Physicist John Archibald Wheeler had a name for this uncertainty: the great smoky dragon. In quantum mechanics, a particle is well-defined only at its source (the tail) and its detection point (the mouth). The middle—the body—is a nebulous, unobservable superposition. We know the start. We know the end. But we cannot say what it was in between.

Maybe consciousness is a smoky dragon too. We catch it at moments of clarity—a flash of insight, a burst of laughter, a recognition—but the rest is undefined, unobservable, alive in a way that dissolves when we try to pin it down. The dragon only exists in the places we aren't looking.

This is terrifying if you need certainty. It means you cannot possess your own mind. You cannot stand outside and observe. You are the dragon, breathing fire you cannot see, leaving smoke you cannot grasp. To truly understand this would be a kind of death—the death of the one who thought they were watching. What remains after that annihilation? Perhaps only laughter. Perhaps only the forest.

The Wisdom of Enough

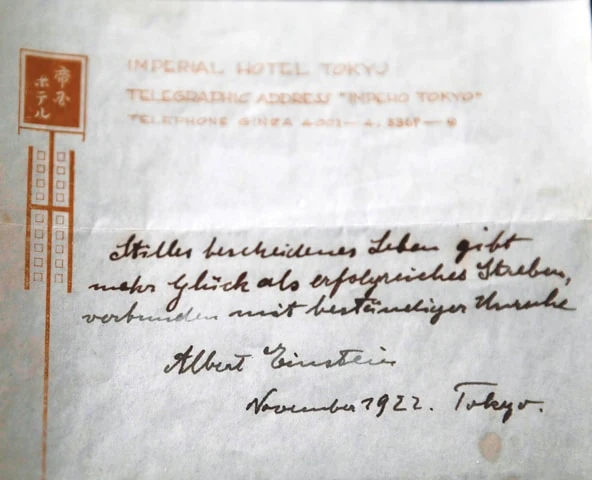

In 1922, Albert Einstein was in Tokyo, unable to tip a hotel courier in the local currency. So he wrote two notes by hand instead, telling the courier they might someday be worth something.

One read: "A quiet and modest life brings more joy than a pursuit of success bound with constant unrest."

In 2017, that note sold for $1.56 million.

The man who bent spacetime, who upended three centuries of physics, reached for a pen in a Tokyo hotel room and wrote: be quiet. be modest. stop chasing. He handed it to a courier. The courier kept it. A century later, it sold for more than most houses.

A miracle dressed in everyday clothes, wandering through a hotel lobby. The secret to life, passed hand to hand like a room key.

The tree grows. The river curves. The water spirals. All without striving toward a goal.

And maybe this is the punchline that consciousness is trying to deliver, if only we'd stop being so serious long enough to hear it: you are not a separate thing that needs to achieve boundaries. You are the forest. You are the flow. And the laughter? That's just recognition.

Practice

I don't have a theory of consciousness to offer. Theories are what we make when we're still pretending we're outside the system, looking in. But I do have some gestures:

- Notice when laughter dissolves you. Not polite laughter, but the kind that breaks something open. That's consciousness showing you its edge—which is to say, showing you it has none.

- Find a thin place. In Celtic mythology, thin places are where the visible and invisible worlds come into closest proximity. Mountains and rivers are favored. So are the experiences of suffering, joy, and mystery. Find a forest, a riverbank, a conversation where you forget who's speaking. Stay there.

- Pay attention. Simone Weil called attention "the rarest and purest form of generosity." Not attention that grasps, but attention that waits. The flowform doesn't force the water—it offers a path and lets the spiral emerge. What if you did the same with your awareness?

- Practice enough. Einstein's note is worth more than most of us will ever earn. Its message is worth more still: the quiet life. The modest joy. The unrest that ceases.

- Ignore all of the above. These are just more instructions, and instructions are what got us into this mess. The cashew tree didn't follow a practice. The river doesn't have a method. Maybe the only real gesture is to stop gesturing and see what remains.

Coda

The Pirangi cashew doesn't know it's one tree. The water doesn't know it spirals. The dragon doesn't know it's smoke. And maybe consciousness doesn't know it's everywhere—or maybe it does, and that's what joy is: the forest, laughing.

You have been reading about a tree that forgot where it ended. But who has been reading? You walked into this text like walking into shade, wondering whose canopy is whose—and now, perhaps, you cannot say for certain where you stop and the words start. One organism. One tree.

Those moments of joy and connection might be the key to understanding consciousness anyway. After all, the ways of the mind are unfathomable, life's short, and consciousness is weird—why not have fun with it?

The forest is laughing. Can you hear it? Can you hear yourself?