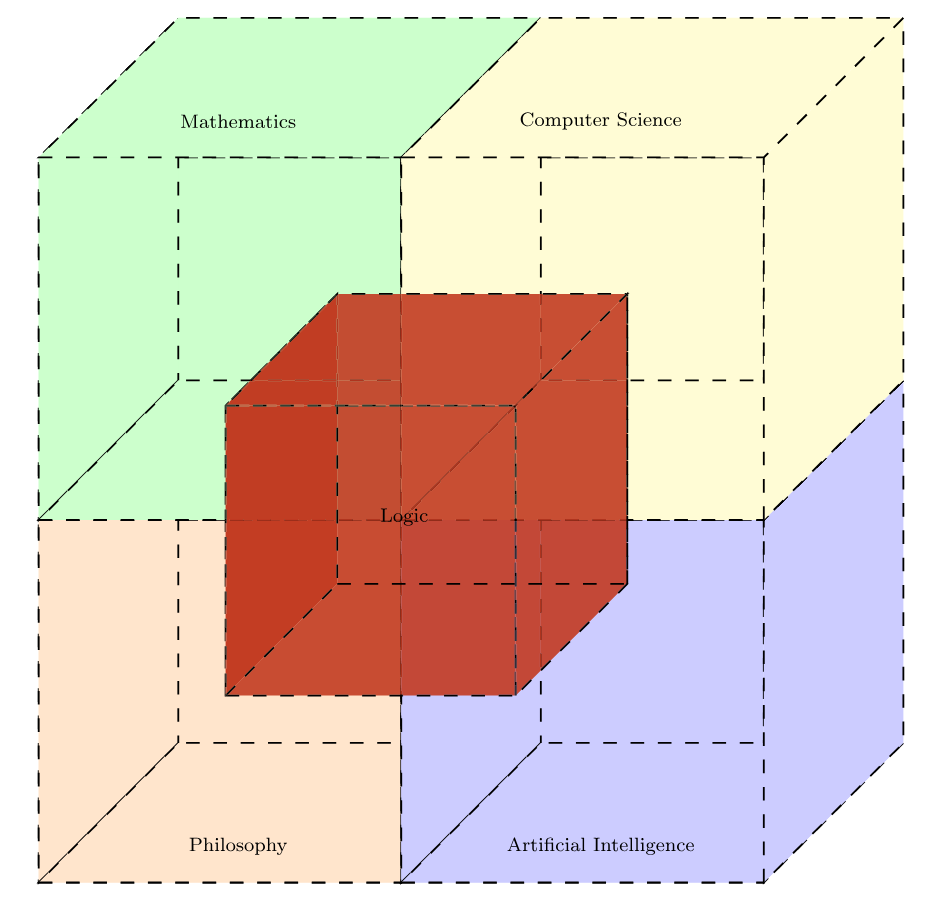

κ_catuskoti: A Meta-Logical Framework for Contradiction-Tolerant, Self-Referential Paradox Computation

Samim.A.Winiger - 5.5.2025

Abstract

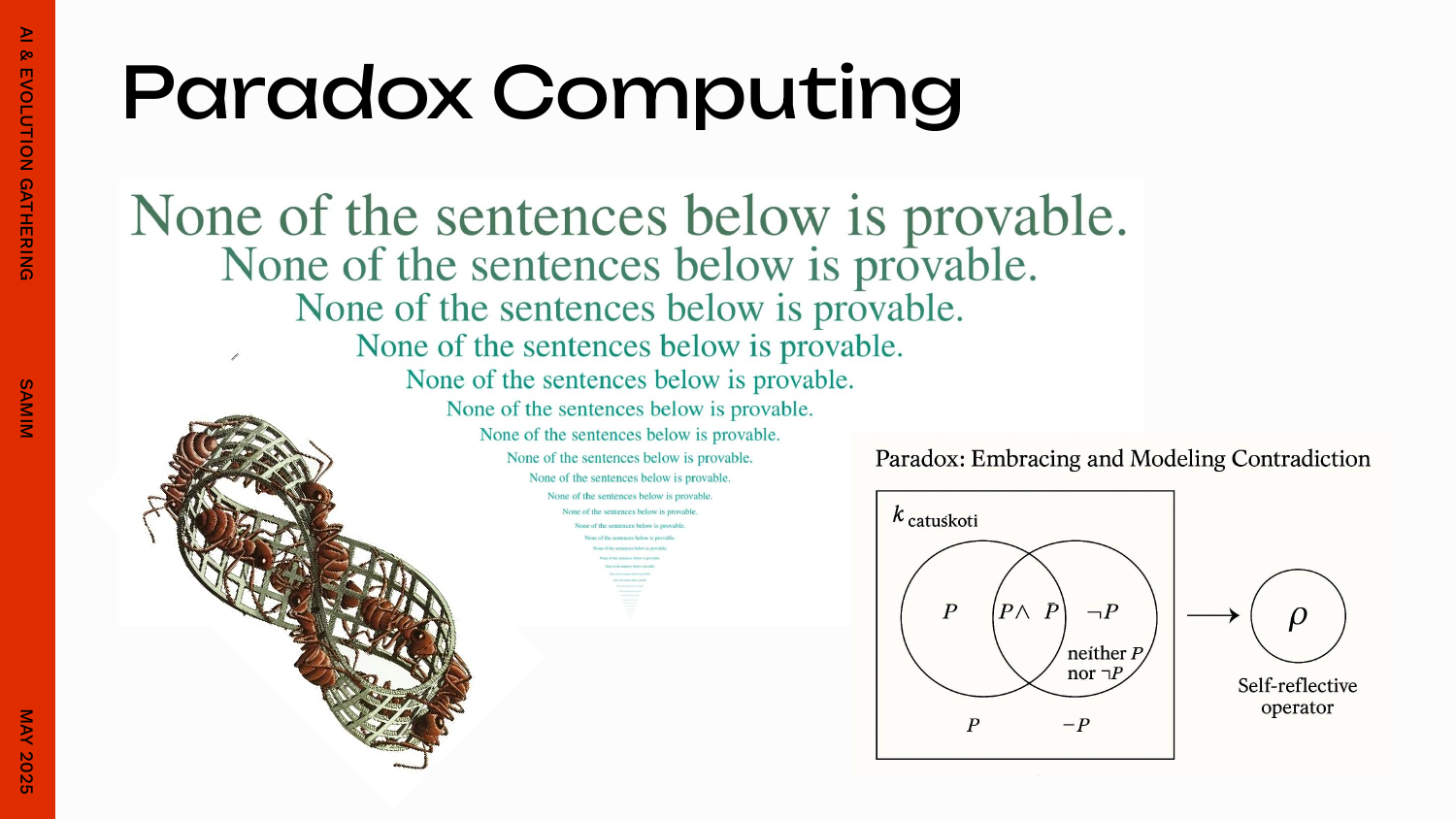

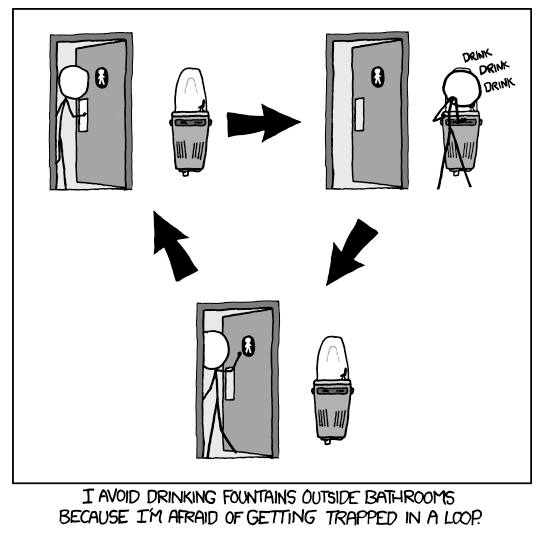

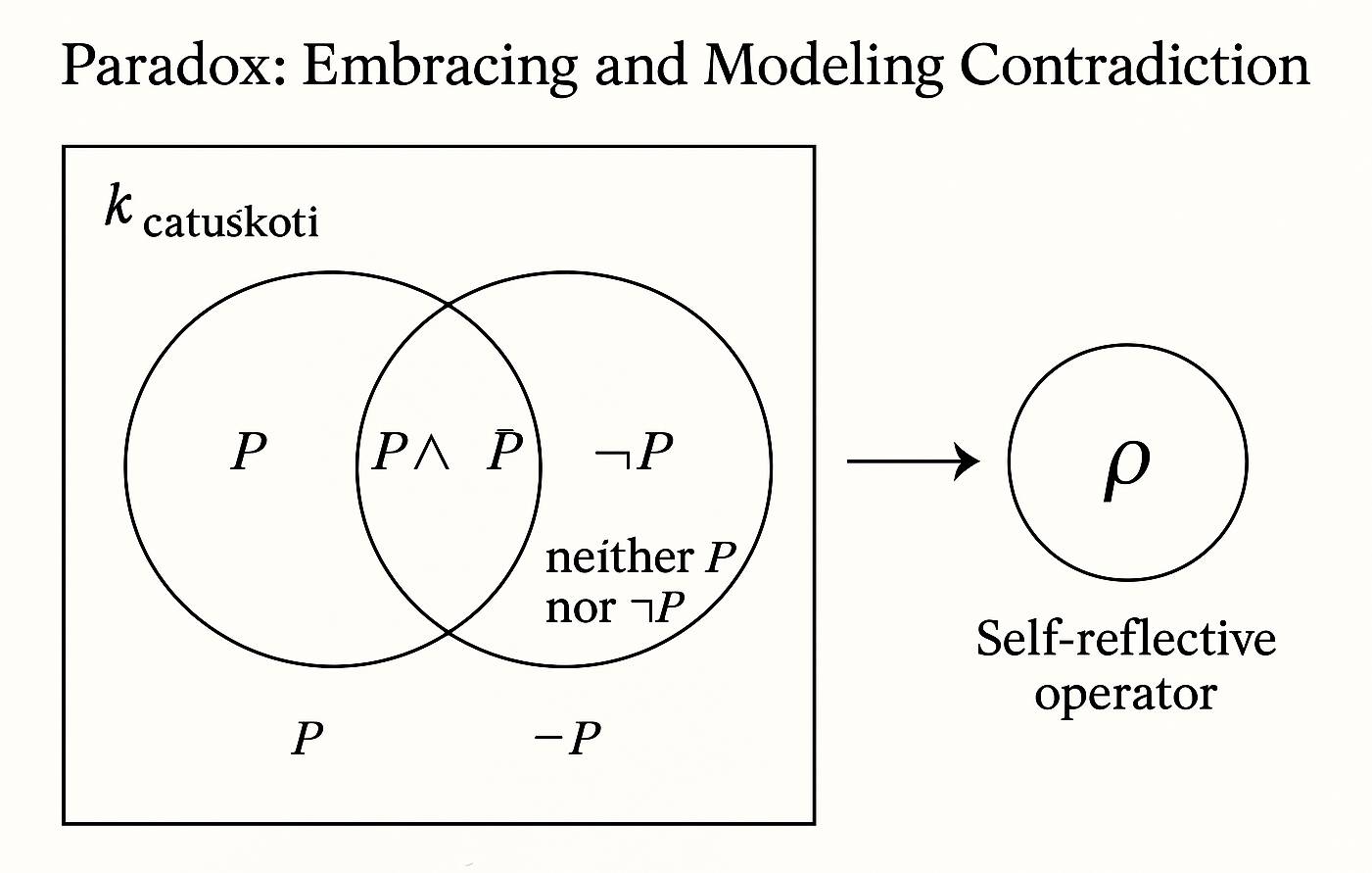

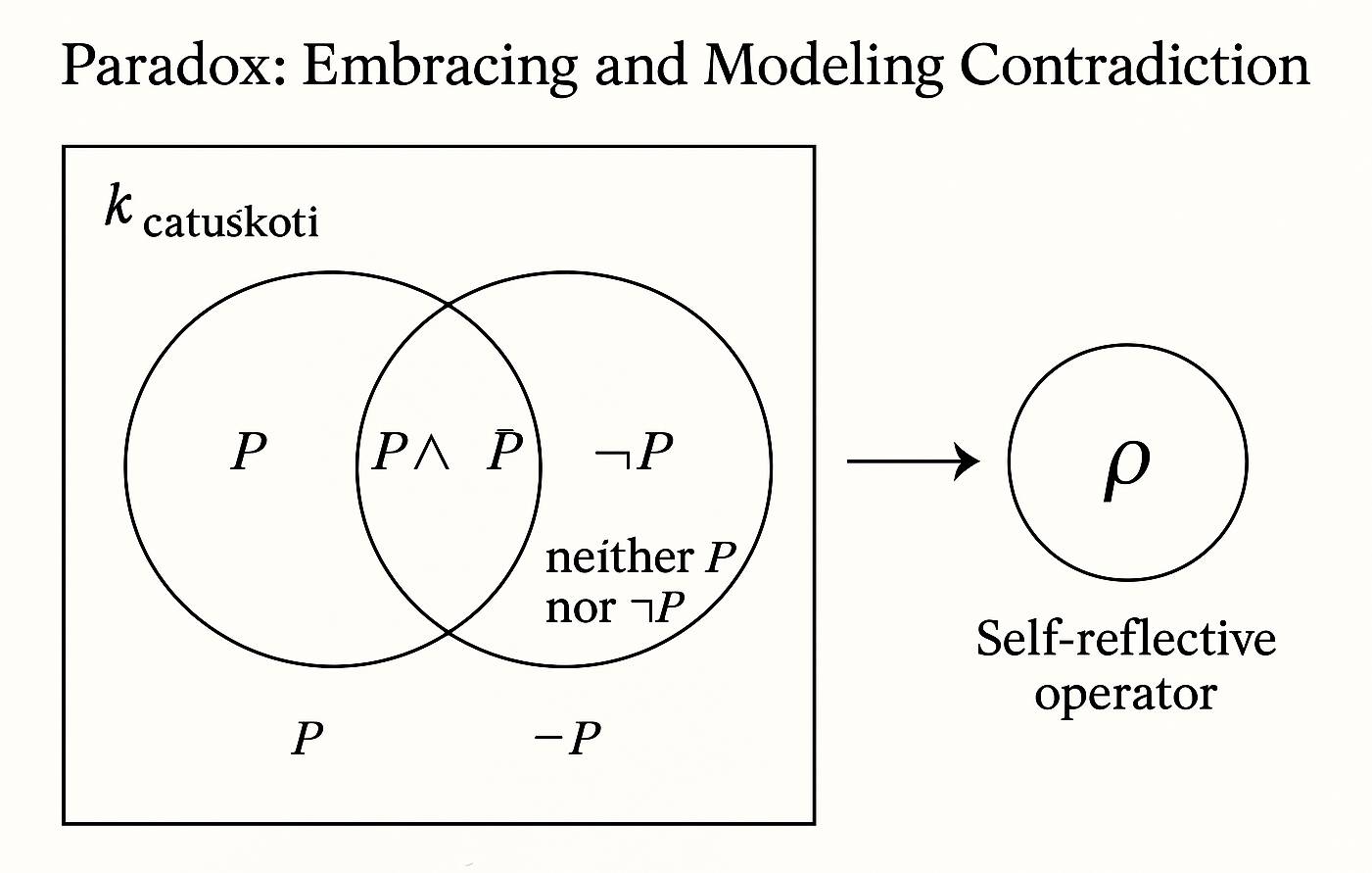

Traditional logic systems, rooted in the binary true/false dichotomy, break down in the presence of paradox, contradiction, and self-reference. Yet such phenomena are not marginal—they are central to language, consciousness, ethics, and the very foundations of mathematics. Inspired by the Buddhist tetralemma _catuskoti_ and informed by developments in paraconsistent and fixed-point logic, we introduce κ_catuskoti: a meta-logical framework that treats paradoxes as structurally navigable rather than fatal flaws.

κ_catuskoti extends standard logic with four truth values—true, false, both, and neither—allowing it to model contradiction \((P \wedge \neg P)\) and indeterminacy (neither P nor ¬P) natively. A key innovation is the self-reflective operator ρ, which enables controlled recursive evaluation of self-referential expressions, including classic paradoxes like the Liar and Russell. We provide a formal syntax, semantics, and computational prototype, and demonstrate the logic’s applicability in reasoning agents, ambiguous ethical scenarios, and meta-linguistic cognition. By parameterizing logical modes with \(\Delta_i\), κ_catuskoti bridges classical, dialetheist, and paraconsistent reasoning. This framework offers a new foundation for logical systems that aim to engage with the complexity of real-world reasoning rather than abstract it away.

_Paradox Computation is simultaneously paradoxical and computational while paradoxically being neither paradoxical nor computational. It computes by not computing and creates paradoxes by resolving them. What is the sound of one hand clapping? Mu!_”

1. Introduction

Classical logic falters in the face of paradox, contradiction, and self-reference. These phenomena are not just edge cases; they permeate natural language, cognition, ethics, and computation. Systems that reject or suppress them risk misrepresenting complex, ambiguous realities. κ_catuskoti addresses this gap by building a formal, contradiction-tolerant logic grounded in Buddhist and paraconsistent traditions, capable of modeling self-reference, oscillation, and epistemic uncertainty. This paper presents the κ_catuskoti framework, including its formal syntax and four-valued semantics, the novel self-reflective operator (\(\rho\)) for handling fixed-point paradoxes, and a computational prototype demonstrating its application to challenging reasoning scenarios.

2. Philosophical Background

The philosophical background of κ_catuskoti weaves together threads from Buddhist logic, paraconsistent logic, and modern self-referential meta-theories, forming a logic that welcomes paradox rather than eliminating it.

2.1. Buddhist Origins: The Catuskoti

From early Buddhist Madhyamaka philosophy, the _catuskoti_ (Sanskrit: चतुष्कोटि, “four corners") breaks with classical binary logic:

For any proposition P, four possibilities exist:

- P (affirmation)

- ¬P (negation)

- P ∧ ¬P (both)

- ¬P ∧ ¬¬P (neither)

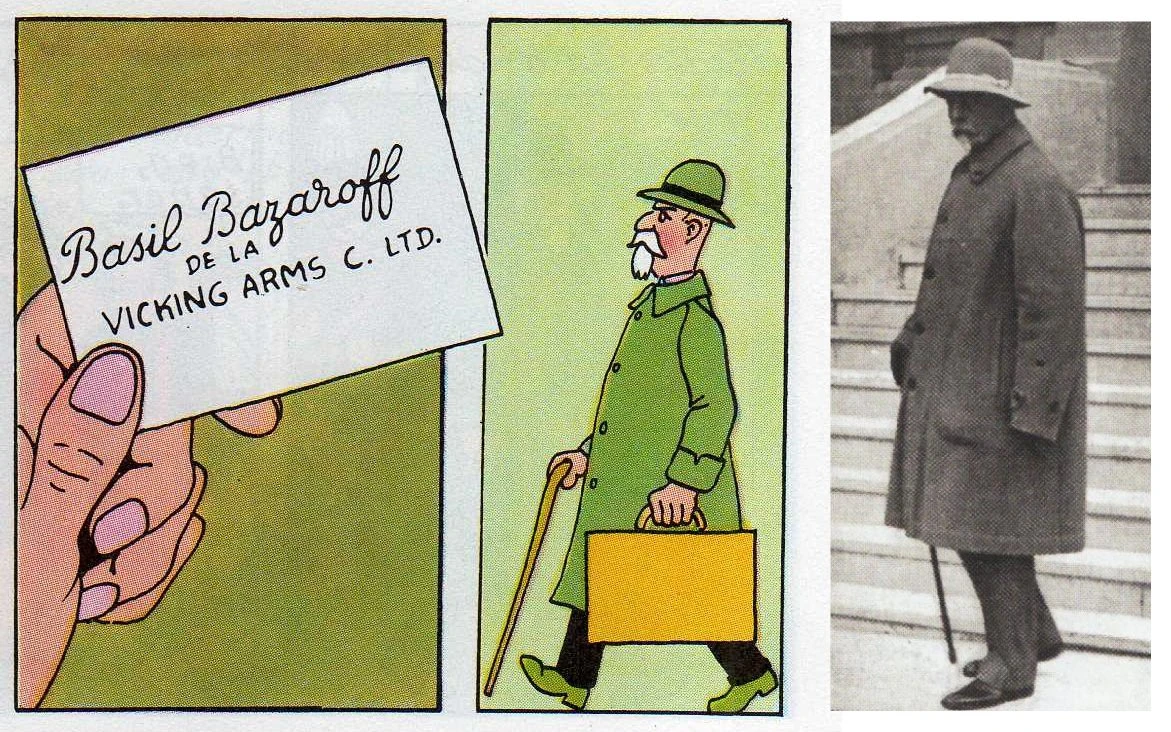

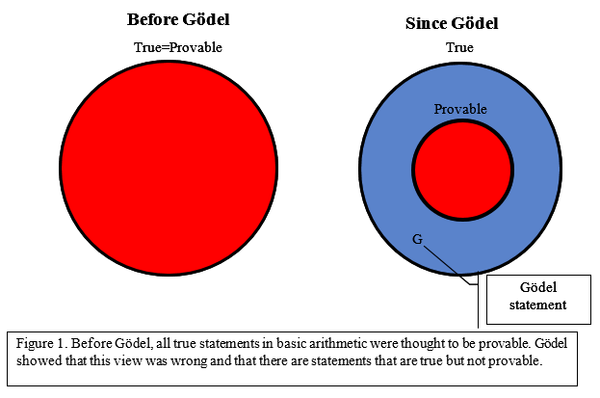

Nāgārjuna, a key philosopher, used this to show the limits of conceptual thought and the emptiness of fixed views. In contrast to Aristotelian logic, which treats contradiction as fatal, _catuskoti_ accepts that some truths are beyond binary classification.[^2]

2.2. Paraconsistency and Dialetheism

Modern paraconsistent logic—developed by thinkers like Graham Priest—allows contradictions to exist without collapsing the system (avoiding _explosion_, where anything can be proven).

- In dialetheism, some contradictions are true (e.g. “This sentence is false").

- κ_catuskoti inherits this tolerance, but adds granularity: not only can P and ¬P both be true, but they can also be indeterminate or change truth-value under context.

2.3. Self-Reference and Meta-Logic

Traditional logic struggles with self-reference:

- The Liar Paradox: “This sentence is false.”

- Russell’s Paradox: The set of all sets that don’t contain themselves.

Most classical solutions involve restrictions or hierarchies (e.g., type theory). But κ_catuskoti, via the ρ operator, embraces self-reference as a native part of reasoning.

ρ allows:

- Fixed-point semantics for paradoxical expressions

- Meta-cognitive stepping outside the system to re-evaluate rules

- Context-sensitive interpretation (via Δ_i)

2.4. Motivations

κ_catuskoti arises from a need to:

- Model ambiguous, paradoxical, or self-referential domains (like natural language, ethics, AI consciousness, or philosophy of mind)

- Build resilient reasoning systems that do not break on contradiction

- Reflect the complexity of real-world cognition and language, which defy classical dichotomies

In essence: κ_catuskoti is not just a formal tool—it’s a philosophical stance:

The world and thought are not always binary. Logic must evolve to match their complexity.

3. Syntax and Semantics of κ_catuskoti

3.1 Syntax

We begin with a classical logical syntax extended with modal and self-referential operators. The language includes atomic propositions, standard Boolean connectives, and two non-classical constructs:

- \(\rho\): a self-reflective operator enabling fixed-point constructions

- \(\Delta_i\): a modal context shift operator, used to tune logical tolerance

The grammar of well-formed formulas is defined recursively:

\[

\phi ::= p \mid \neg\phi \mid (\phi \wedge \phi) \mid (\phi \vee \phi) \mid (\phi \rightarrow \phi) \mid \rho(\phi) \mid \Delta_i(\phi)

\]

3.2 Semantics

3.2.1 Truth Values and Valuation

The κ_catuskoti logic operates over a four-valued semantic domain:

\[

\mathbb{V} = \{\top, \bot, \mathbb{B}, \mathbb{N}\}

\]

Each value corresponds to a distinct logical state:

- \(\top\): true

- \(\bot\): false

- \(\mathbb{B}\): both true and false (contradictory)

- \(\mathbb{N}\): neither true nor false (indeterminate)

A valuation function \(v : \Phi \to \mathbb{V}\) assigns each formula a value in this domain.

3.2.2 Semantics of Connectives

Let \(\phi, \psi \in \Phi\) and define:

For the definitions of conjunction, disjunction, and implication that follow, the conditions within each cases block are to be evaluated in order from top to bottom. The first condition that holds true determines the semantic value of the expression.

Negation

\[

v(\neg \phi) =

\begin{cases}

\bot & \text{if } v(\phi) = \top \\

\top & \text{if } v(\phi) = \bot \\

\mathbb{B} & \text{if } v(\phi) = \mathbb{B} \\

\mathbb{N} & \text{if } v(\phi) = \mathbb{N}

\end{cases}

\]

Conjunction

\[

v(\phi \wedge \psi) =

\begin{cases}

\bot & \text{if } \bot \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\mathbb{N} & \text{if } \mathbb{N} \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\mathbb{B} & \text{if } \mathbb{B} \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\top & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}

\]

Disjunction

\[

v(\phi \vee \psi) =

\begin{cases}

\top & \text{if } \top \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\mathbb{B} & \text{if } \mathbb{B} \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\mathbb{N} & \text{if } \mathbb{N} \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\bot & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}

\]

Implication (material conditional)

\[

v(\phi \rightarrow \psi) =

\begin{cases}

\top & \text{if } v(\phi) = \bot \text{ or } v(\psi) = \top \\

\mathbb{B} & \text{if } \mathbb{B} \in \{v(\phi), v(\psi)\} \\

\mathbb{N} & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}

\]

_(Note: The precise definitions for conjunction, disjunction, and implication in many-valued logics can vary. These represent one possible formalization; specific use cases might warrant alternative definitions, such as those based on lattices like First Degree Entailment.)_

3.2.3 Interpretive Commentary

This truth system allows κ_catuskoti to explicitly represent logical uncertainty and paradox. For example, a contradictory claim such as “The court both ruled and did not rule on the case” can be assigned the value \(\mathbb{B}\), whereas a vague or ill-defined claim such as “Justice is red” might be interpreted as \(\mathbb{N}\).

Operators behave intuitively based on the definitions above: Negation flips \(\top\) and \(\bot\), leaving \(\mathbb{B}\) and \(\mathbb{N}\) unchanged. The behavior of conjunction and disjunction prioritizes certain values (e.g., \(\bot\) for conjunction, \(\top\) for disjunction). Implication is defined conservatively.

These design choices maintain non-explosiveness—that is, the logic resists collapse under contradiction, a key feature inherited from paraconsistent principles.

3.3 Self-Reference and the ρ Operator

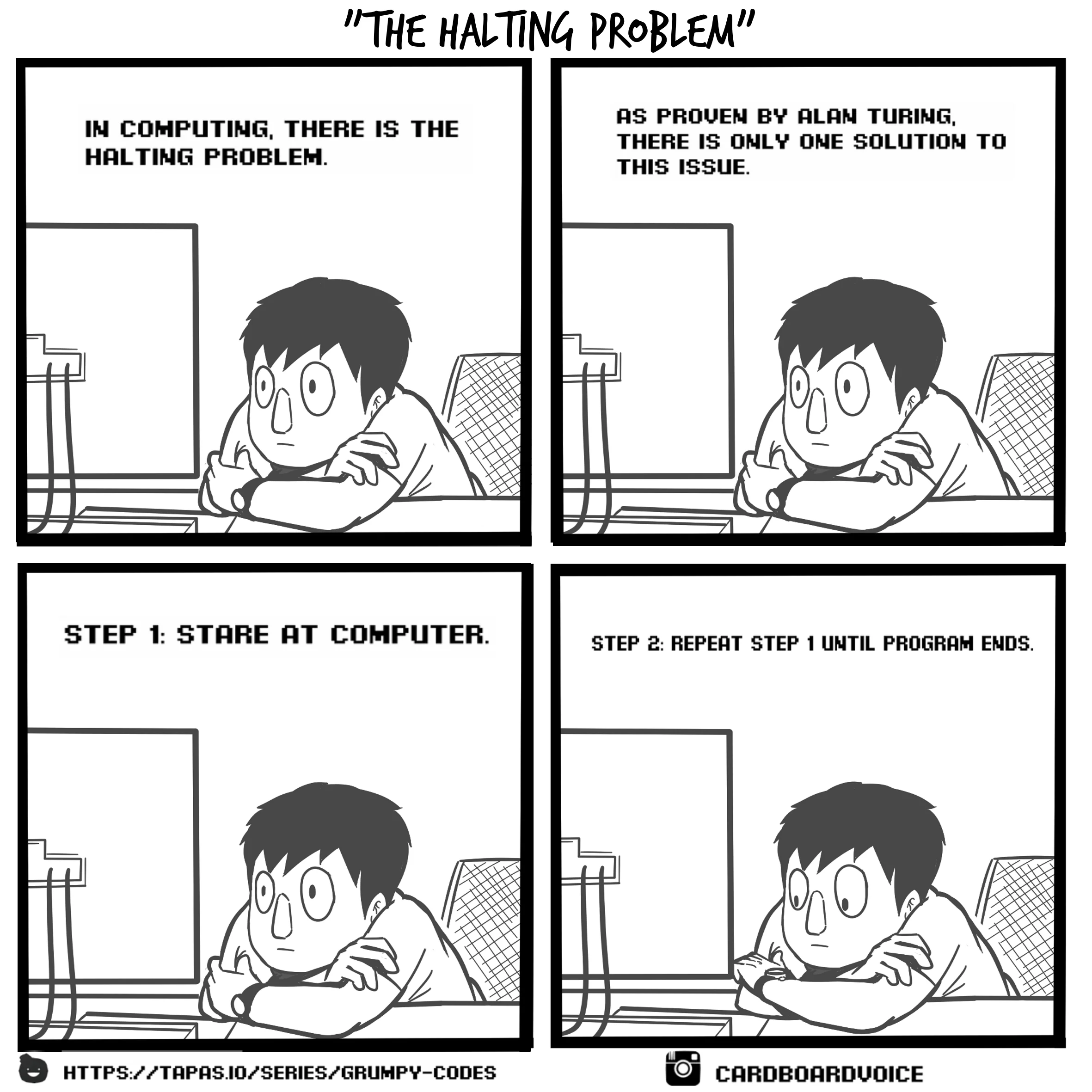

3.3.1 Fixed-Point Semantics

The \(\rho\) operator enables formulas to refer to themselves in a controlled manner. Formally, we define \(\rho(\phi)\) notionally as the fixed point of the operation represented by \(\phi(x)\), where \(x\) conceptually stands for the formula \(\rho(\phi)\) itself. That is, \(\rho(\phi)\) seeks a truth value \(v^{\ast} \in \mathbb{V}\) such that applying the logical operation defined by \(\phi\) to \(v^{\ast} \) yields \(v^{\ast} \) again.

This semantic interpretation is constructed iteratively. We define an evaluation sequence starting with an initial value (e.g., \(\top\) as a convention):

\[

v^{(0)}(\rho(\phi)) := \top

\]

\[

v^{(n+1)}(\rho(\phi)) := v(\phi[v^{(n)}(\rho(\phi)) / x])

\]

Here, \(v(\phi[v’ / x])\) represents the semantic evaluation of the formula structure \(\phi\) where the placeholder \(x\) (representing the value of \(\rho(\phi)\)) is assigned the value \(v’\) from the previous iteration. The process continues until the sequence of values \(v^{(0)}, v^{(1)}, v^{(2)}, \dots\) stabilizes.

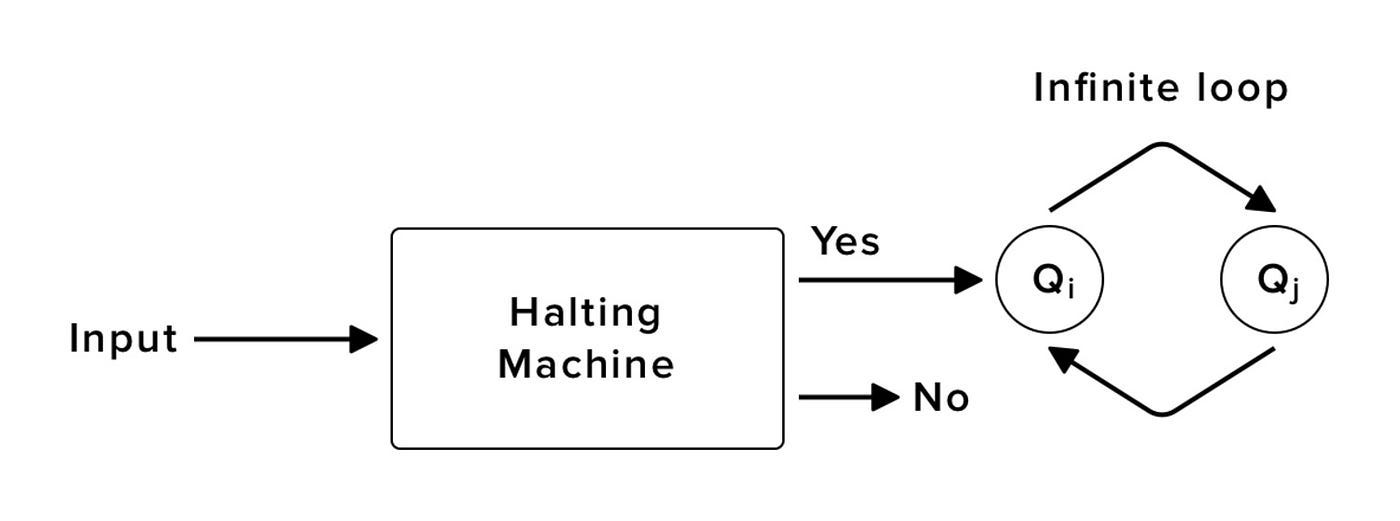

- If the sequence converges to a single value \(v^{\ast} \in \mathbb{V}\) (i.e., \(v^{(k+1)} = v^{(k)} = v^{\ast} \) for some \(k\)), we assign \(v(\rho(\phi)) = v^{\ast} \).

- If the sequence enters a stable oscillation (e.g., cycling between \(\top\) and \(\bot\)), we assign \(v(\rho(\phi)) = \mathbb{B}\).

- If the sequence diverges or shows no clear convergent or oscillatory pattern within a predefined computational bound, we may assign \(v(\rho(\phi)) = \mathbb{N}\).

This formalism allows the system to represent and reason about paradoxes internally.

3.3.2 Example: The Liar Sentence

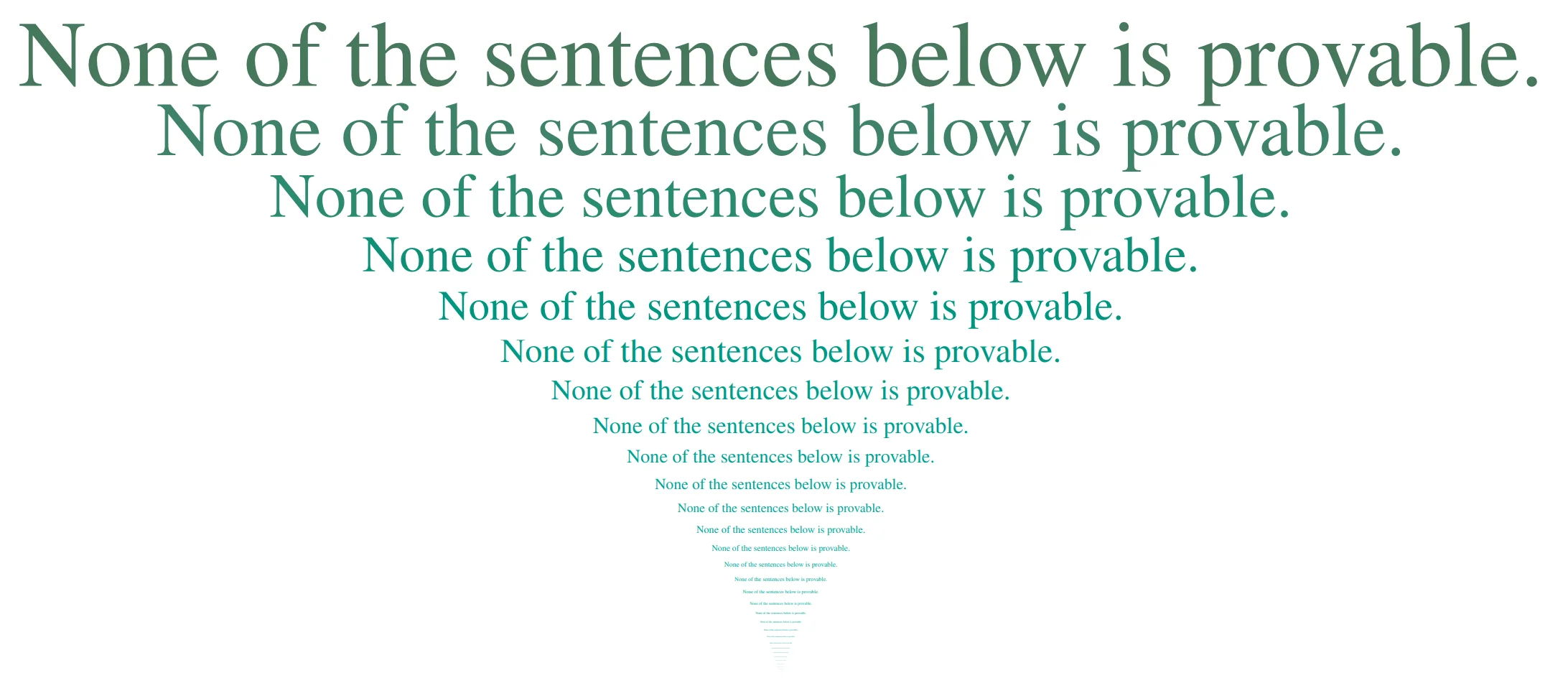

We define the Liar Sentence \(L\) as a formula that asserts its own negation, using the \(\rho\) operator:

\[

L := \rho(x). \neg x

\]

Evaluated iteratively, starting with \(v^{(0)}(L) = \top\):

- \(v^{(1)}(L) = v(\neg \top) = \bot\)

- \(v^{(2)}(L) = v(\neg \bot) = \top\)

- \(v^{(3)}(L) = v(\neg \top) = \bot\)

- … and so on.

The sequence \(\top, \bot, \top, \bot, \dots\) oscillates indefinitely. According to the rule for stable oscillation:

\[

v(L) = \mathbb{B}

\]

3.3.3 Interpretive Commentary

The \(\rho\) operator formalizes self-reference as a truth-evaluable process. Rather than banning paradoxes like the Liar or Russell’s Set (which would require a set-theoretic formulation), κ_catuskoti models their semantic dynamics directly. This iterative approach aligns with established fixed-point semantics for truth predicates, notably Kripke’s theory of truth (Kripke, 1975), and the dynamic perspective of revision theories (Gupta & Belnap, 1993), which also use stage-based evaluations to handle semantic paradoxes. This enables paradox to be treated as a computationally tractable phenomenon rather than a fatal flaw.

Optionally, one can formulate \(\rho\) using category theory by treating \(\mathbb{V}\) as an object in a semantic category, and \(\rho\) as related to fixed-point constructions like those found via coalgebraic methods. This perspective may provide future generalizations.

3.4. Context Sensitivity: The \(\Delta_i\) Operator

To handle shifts in perspective or context, crucial for interpreting many koans or evolving knowledge bases, we introduce the context-shifting operator, \(\Delta_i\). This operator is intended to allow the logic to dynamically alter the interpretation or significance of propositions based on a specified context \(i\).

For example, \(\Delta{zen}\) \(( Paradox )\) might evaluate a paradox within a ‘Zen’ context where its contradictory nature is embraced (Value B or N), while \(\Delta{classical}\) \(( Paradox )\) might force a rejection (Value F, depending on underlying assumptions). The \(\Delta_i\) operator represents a mechanism for modulating semantic evaluation based on external or meta-level considerations.

While the intuitive role of \(\Delta_i\) in enabling modal flexibility and context-dependent reasoning is clear, providing its full formal semantics—detailing precisely how it interacts with the valuation function \(v\) and the \(\rho\) operator across different contexts \(i\)—remains a significant avenue for future research. Its inclusion here signals a key direction for extending the core logic’s expressiveness.

4. Illustrative Examples

Here are three practical examples of the κ_catuskoti logic in action, across different domains where contradiction, indeterminacy, or self-reference must be modeled directly:

4.1 Natural Language Semantics (Liar Paradox)

Sentence:

“This sentence is false.”

Classical logic:

Breaks due to self-reference:

- If it’s true, then it’s false.

- If it’s false, then it’s true.

κ_catuskoti logic:

Encode as a fixed-point, as shown in Section 3.3.2:

\(L := \rho(x). \neg x\)

Evaluate under the four-valued semantics using the iterative \(\rho\) process:

- The evaluation results in a stable oscillation (\(\top \leftrightarrow \bot\)).

- Thus, \(v(L) = \mathbb{B}\) (both true and false).

Use case: Formalizing semantics for natural language, analyzing paradoxical statements in text, potential applications in truth valuation for generative models.

4.2 Ethics or Legal Reasoning (Contradictory Norms)

Scenario:

An act is judged according to conflicting principles. For example:

“Whistleblowing is both an act of integrity (fulfilling a duty to expose wrongdoing) and an act of betrayal (breaking loyalty oaths).”

Classical logic:

Forces a resolution to either true or false, potentially oversimplifying the dilemma. If represented as \(P \wedge \neg P\), the system risks explosion.

κ_catuskoti logic:

Model the core propositions:

\(P := “The act (whistleblowing) is permissible/good"\)

Assign the contradictory value based on the scenario:

\(v(P) = \mathbb{B}\) (both)

A reasoning system using κ_catuskoti can then use this value:

- Acknowledge the conflict without system collapse.

- Apply different meta-rules based on context, possibly using the \(\Delta_i\) operator:

- In \(\Delta_1\) (e.g., a pluralist ethical mode), the state \(\mathbb{B}\) might be accepted as representing a genuine dilemma.

- In \(\Delta_0\) (e.g., a strict legal mode requiring a single verdict), the state \(\mathbb{B}\) might trigger a specific procedure (e.g., referral, declaring a mistrial, applying a tie-breaking rule).

Use case: Modeling complex ethical dilemmas, AI safety and alignment (handling conflicting values), legal reasoning systems dealing with ambiguous statutes or precedents.

4.3 AI Self-Modeling / Metacognition (Epistemic Uncertainty)

Scenario:

An AI agent needs to represent its own uncertainty about a belief it holds.

“The agent assesses its belief state regarding proposition X as unreliable or indeterminate.”

Classical modal logic: Typically represents belief (\(B(X)\)) or lack of belief (\(\neg B(X)\)), but struggles to natively represent a state of acknowledged indeterminacy about X itself without extensions.

κ_catuskoti logic:

Let \(\phi\) represent the proposition “The agent has conclusive evidence for/against X”.

- If a meta-assessment process evaluates the evidence regarding X (or the reliability of the reasoning process itself) as inconclusive, contradictory, or ill-defined, the agent can directly assign the value \(\mathbb{N}\) to the relevant proposition reflecting this assessment.

- For instance, assigning \(v(\phi) = \mathbb{N}\) explicitly represents the agent’s state of indeterminacy regarding its conclusion about X.

Allowing propositions to be assigned \(\mathbb{N}\) enables the system to explicitly represent states of doubt, ambiguity, or acknowledged ignorance. This facilitates more nuanced self-reflection and can trigger appropriate behaviors, such as seeking more information rather than acting on an uncertain conclusion. While the \(\rho\) operator _could_ be used for more complex recursive self-assessments (e.g., “I believe that my belief is indeterminate"), the direct use of \(\mathbb{N}\) already provides a powerful tool for representing basic epistemic uncertainty.

Use case: Building more introspective AI agents, modeling cognitive dissonance or uncertainty in cognitive science, developing robust agents for environments with highly uncertain or deceptive information.

5. Computational Implementation

While κ_catuskoti is primarily a theoretical framework, its potential computational applications motivate exploring its implementation. A prototype system can demonstrate its feasibility and allow for empirical testing.

A basic prototype has been developed in Python to explore the core mechanics. The evaluation process centers around a function, conceptually evaluate_rho(formula, max_iterations), which applies the semantic rules iteratively for self-referential formulas containing \(\rho\). It tracks the sequence of truth values assigned in each iteration up to a predefined limit (max_iterations) to determine convergence (to T, F, B) or divergence (assigned N). Standard test cases, such as the Liar Paradox formulated as L: \rho(\neg L), were used to validate the mechanism, confirming its ability to assign the expected paradoxical value (B in this case, assuming convergence within the iteration limit).

5.1 Core Components

The engine includes implementations for:

- Four Truth Values: Representation of \(\top\) (TRUE), \(\bot\) (FALSE), \(\mathbb{B}\) (BOTH), and \(\mathbb{N}\) (NEITHER).

- Logical Connectives: Functions evaluating negation (\(\neg\)), conjunction (\(\wedge\)), disjunction (\(\vee\)), and implication (\(\rightarrow\)) based on the defined semantics (Section 3.2.2).

- \(\rho\) Operator Evaluation: An iterative process to compute fixed points for self-referential formulas involving \(\rho\), handling convergence, oscillation (assigning \(\mathbb{B}\)), and potential divergence (assigning \(\mathbb{N}\)), as described in Section 3.3.1.

- \(\Delta_i\) Operator (Conceptual): While the prototype focuses on the core paraconsistent mode, the structure allows for future extension with the \(\Delta_i\) operator to simulate different logical modes (e.g., classical, dialetheist) by altering evaluation rules.

- (Optional) Truth Table Visualization: The prototype includes utilities to generate and display the full truth tables for the implemented connectives across the four-valued domain.

5.2 Example: Simulated Agent Reasoning

The prototype allows simulating how an AI agent equipped with κ_catuskoti logic might handle contradictory or indeterminate information. Consider an agent evaluating safety conditions:

- If evidence regarding condition X is contradictory (e.g., sensor reports safe and unsafe), the logic assigns \(v(\text{X_is_safe})\) = \(\mathbb{B}\). The agent’s policy might map \(\mathbb{B}\) to a cautious action: "Proceed with caution".

- If evidence for condition Y is clearly positive, \(v(\text{Y_is_safe})\) = \(\top\). The agent proceeds confidently: "Proceed".

- If evidence for condition Z is insufficient or fundamentally ambiguous, \(v(\text{Z_is_safe})\) = \(\mathbb{N}\). The logic acknowledges this indeterminacy, potentially leading the agent to halt: "Do not proceed; seek clarification".

This simulation highlights how κ_catuskoti enables nuanced decision-making, allowing agents to recognize and react appropriately to contradiction and indeterminacy rather than defaulting to arbitrary choices or system failure.

6. Applications and Implications

The κ_catuskoti framework, with its capacity to handle contradiction, indeterminacy, and self-reference, opens significant applications across diverse fields.

- Artificial Intelligence: A primary application lies in building more robust AI reasoning systems. Agents equipped with κ_catuskoti can operate in complex environments with conflicting or incomplete information without crashing or resorting to arbitrary conflict resolution. This is crucial for decision-making under uncertainty, fusing contradictory sensor data, or navigating environments with deceptive information. It offers a path towards AI that can acknowledge and manage ambiguity rather than simply rejecting it.

- Cognitive Science: The logic provides formal tools for modeling aspects of human cognition that are challenging for classical systems. This includes phenomena like cognitive dissonance, ambivalence (holding conflicting beliefs or desires), managing dissociation, and potentially the recursive nature of self-awareness or meta-cognition, as explored in the AI self-modeling example (Section 4.3).

- Ethics and Law: κ_catuskoti allows for the formal representation of genuine ethical dilemmas or legal situations where conflicting principles or perspectives are equally valid (as illustrated in Section 4.2). Instead of forcing a premature resolution, the logic can maintain the contradictory state (\(\mathbb{B}\)) or indeterminate state (\(\mathbb{N}\)), enabling systems or analyses that explicitly acknowledge and reason about these conflicts, potentially reflecting pluralistic viewpoints more faithfully.

- Philosophy of Language and Semantics: The framework offers a way to analyze and assign semantic values to paradoxical utterances (like the Liar Paradox, Section 4.1) and potentially address issues of vagueness or boundary cases where predicates may seem to both apply and not apply, or neither apply nor not apply.

In essence, κ_catuskoti provides a foundation for systems that engage more directly with the paradoxical and ambiguous nature of real-world information and reasoning processes, moving beyond the limitations of purely binary logic.

7. Comparison with Related Systems

To situate κ_catuskoti within the landscape of existing logical frameworks, it is useful to compare its capabilities against related systems. Notably, the four-valued semantics employed here share the same truth values \({\top, \bot, \mathbb{B}, \mathbb{N}}\) as Nuel Belnap’s influential logic of First Degree Entailment (FDE), often used in computer science to handle inconsistent and incomplete information (Belnap, 1977).

However, while sharing this foundational structure, κ_catuskoti introduces crucial distinctions:

- Dynamic Self-Reference Handling (\(\rho\) Operator): Unlike standard FDE, which is primarily concerned with static entailment between formulas that might contain inconsistent/incomplete information, κ_catuskoti introduces the \(\rho\) operator to explicitly model and evaluate _self-referential* statements dynamically. Its iterative semantics provide a mechanism for determining the truth value of paradoxical sentences within the four-valued framework.

- Comparison to Kripke’s Theory of Truth: Kripke’s fixed-point semantics (1975) also provides a powerful way to handle self-reference, often over a three-valued logic (True, False, Undefined/Grounded). κ_catuskoti differs in its foundational four-valued structure (explicitly acknowledging Both/Contradiction) and, significantly, in how the \(\rho\) operator’s iterative process can terminate by assigning \(\mathbb{N}\) (Neither) to certain non-converging or oscillating cases (within a computational bound), rather than leaving them ungrounded or undefined in precisely the same way as Kripke’s minimal fixed point.

- Comparison to Revision Theory: Gupta and Belnap’s Revision Theory of Truth (1993) also uses an iterative process, but focuses on how the semantic status of paradoxical sentences (like the Liar) _revises_ over stages of evaluation, often resulting in non-stable or cyclically changing classifications. While \(\rho\)’s iteration shares similarities, κ_catuskoti aims to assign a _single* final value from \({\top, \bot, \mathbb{B}, \mathbb{N}}\) based on the iteration’s behavior (convergence or bounded oscillation/divergence), offering a different end-state classification compared to the typical outcomes in Revision Theory.

- Context Sensitivity (\(\Delta_i\) Operator): The conceptual \(\Delta_i\) operator (whose full formalization is future work, see Sec 3.4) aims to provide a built-in mechanism for context-dependent evaluation, a feature not typically integrated directly into the core semantics of FDE, Kripke’s theory, or standard Revision Theory.

The following table summarizes key feature differences across several logical paradigms:

| Logic System |

Contradiction |

Indeterminacy |

Self-Reference |

Dynamic Semantics |

| Classical Logic |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

| Fuzzy Logic |

✘ |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

| Paraconsistent Logic |

✓ |

✘ |

partial [^1] |

✘ |

| Modal μ-calculus |

✘ |

✘ |

✓ |

✓ |

| κ_catuskoti |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

8. Limitations and Future Work

While the κ_catuskoti framework presented here offers a novel approach to handling paradox and inconsistency, it represents foundational work with several avenues for further development. We identify the following key limitations and directions for future research:

- Proof Theory: This paper has focused on the syntax and semantics of κ_catuskoti. A significant next step is the development of a corresponding proof theory—a formal deductive system (e.g., natural deduction, sequent calculus, or axiomatic system) that precisely captures the logic’s entailment relation. This is crucial for formal verification and automated reasoning applications.

- Quantification: The current formulation is propositional. Extending κ_catuskoti to include first-order or higher-order quantification would significantly increase its expressive power, allowing reasoning about objects, properties, and relations, but would also require careful consideration of how quantifiers interact with the four-valued semantics and the \(\rho\) operator.

- Convergence Properties of \(\rho\): The iterative semantics for the \(\rho\) operator guarantee finding fixed points or detecting oscillation in finite domains or under certain conditions. However, a more rigorous formal analysis is needed to characterize the convergence properties of \(\rho\) under various constraints, especially for potentially infinite iterations or more complex formula structures. Establishing conditions for guaranteed termination or identifying classes of formulas with predictable behavior is an important theoretical goal.

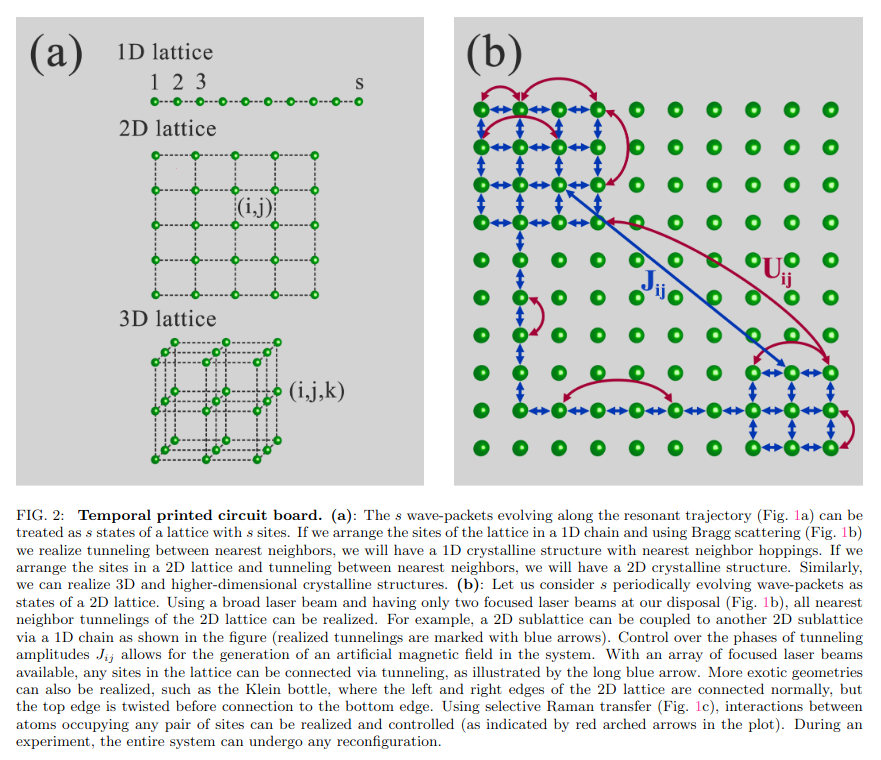

- Machine Learning Integration: The capacity of κ_catuskoti to handle contradictory and uncertain information suggests intriguing possibilities for integration with machine learning models. Future work could explore using κ_catuskoti as a meta-reasoning layer for large language models (LLMs) to improve their handling of inconsistent inputs or to allow them to represent their own uncertainty more explicitly (perhaps connecting to research on calibrating model confidence). Investigating learnable versions of the \(\Delta_i\) modal shifts is another potential direction.

Addressing these areas would further mature κ_catuskoti as both a theoretical framework and a practical tool for advanced reasoning systems.

9. Conclusion

κ_catuskoti logic offers a radical yet rigorous reconceptualization of logical foundations: one that embraces contradiction, supports indeterminacy, and renders paradox productive. By synthesizing Buddhist tetralemmic thought with modern fixed-point meta-logic and four-valued semantics, this system reframes long-standing philosophical and computational limitations. The introduction of the \(\rho\) operator allows for dynamic, recursive truth evaluation, making κ_catuskoti uniquely suited for domains where self-reference and epistemic instability are the norm, not the exception.

Our computational prototype demonstrates how an AI agent using κ_catuskoti can reason coherently in contradictory environments—a capacity increasingly relevant for systems interacting with complex, conflicting human data. This logic not only resists the collapse of classical systems under paradox but transforms paradox into an epistemic resource. Looking ahead, κ_catuskoti opens promising avenues for machine consciousness, legal and moral pluralism, and robust epistemology under uncertainty. In rejecting the tyranny of the excluded middle, it brings logic one step closer to the way real minds—and real worlds—work.

References

- Belnap, Nuel D. – _A Useful Four-Valued Logic_ (1977) _In Modern Uses of Multiple-Valued Logic, ed. J. Michael Dunn and George Epstein._

- Bieberich, Erhard – _What the Liar Paradox Can Reveal About the Quantum Logical Structure of Our Minds_ (2001) [arXiv]

- Chaitin, Gregory – _The Unknowable_ (1999)

- da Costa, Newton C.A. – _Paraconsistent Logic: Consistency, Contradiction and Negation_ (2010)

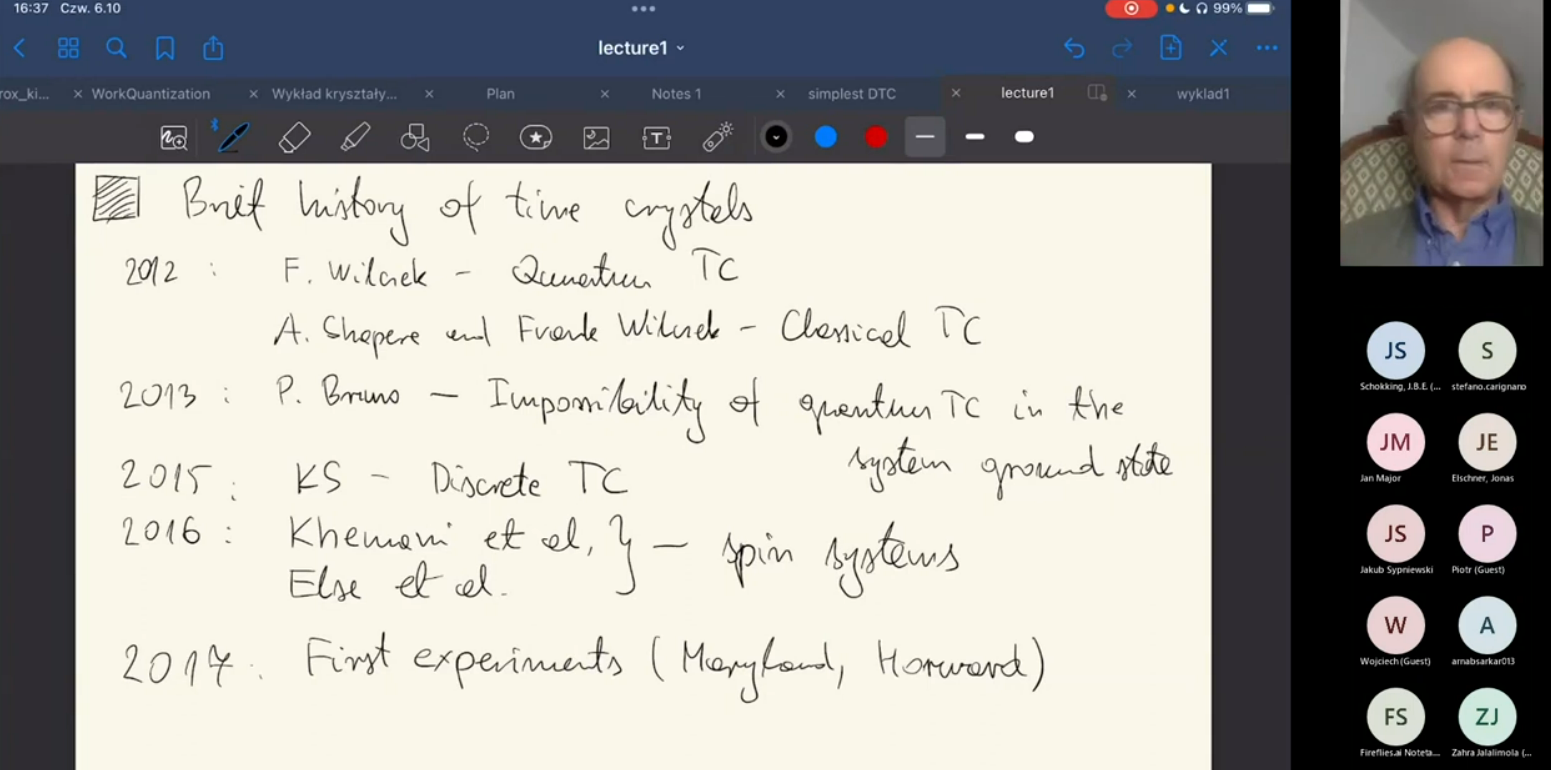

- Hofstadter, Douglas – _Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid_ (1979)

- Hofstadter, Douglas – _I Am a Strange Loop_ (2007)

- Gupta, Anil, and Belnap, Nuel – _The Revision Theory of Truth_ (1993)

- Kripke, Saul A. – _Outline of a Theory of Truth_ (1975) _Journal of Philosophy, 72(19), 690-716._

- Matilal, B.K. – _The Central Philosophy of Buddhism_ (1986)

- Priest, Graham – _In Contradiction: A Study of the Transconsistent_ (1987)

- Prokopenko, Mikhail et al. – _Self-Referential Basis of Undecidable Dynamics_ (2017) [arXiv]

- Robinson, Richard H. – _Some Logical Aspects of Nagarjuna’s System_ (1957)

- Szpiro, George – _Perplexing Paradoxes: Unraveling Enigmas in the World Around Us_ (2024)

- Yanofsky, Noson S. – _A Universal Approach to Self-Referential Paradoxes, Incompleteness and Fixed Points_ (2003) [arXiv]

- Zizzi, Paola A. – _Turning the Liar Paradox into a Metatheorem of Basic Logic_ (2007) [arXiv]

Additional Resources

For further context and related topics, readers may find the following resources and areas of exploration helpful:

- Berry Paradox – Wikipedia Article (Wikipedia)

- Catuṣkoṭi – Wikipedia Article (Wikipedia)

- Grelling–Nelson Paradox – Wikipedia Article (Wikipedia)

- Foundations of Many-Valued Logic: Works by Jan Łukasiewicz.

- Paraconsistent Logic (Further Developments): Contributions by Richard Routley (Sylvan) and Ross Brady.

- Dialetheism (Further Perspectives): Writings by J.C. Beall and Peter Mortensen.

- Algebraic Structures for Many-Valued Logic: Research on bilattices by Melvin Fitting, Ofer Arieli, and Arnon Avron.

- Four-Valued Logic (Further Theory): Contributions by J. Michael Dunn.

- Classical Approaches to Paradox: Theories of truth and hierarchical solutions by Alfred Tarski and Saul Kripke.

- Nāgārjuna’s Philosophy: Direct engagement with primary texts like the _Mūlamadhyamakakārikā_.